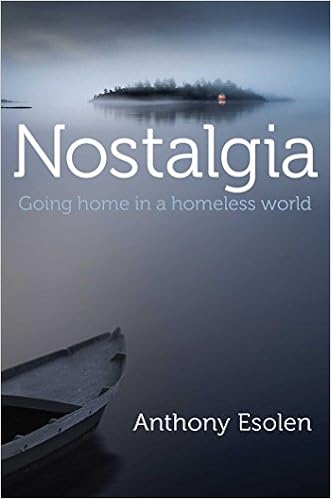

This book has been terrific. The publisher, Regnery (really good) sent it and, at the last moment before I headed out the door to begin this trip, I slid it into the outside pocket of my suitcase. It isn’t released yet (30 October). Over the last few days, I have been reading and savoring subsections of chapters. This is one of those books that you have to read a bit at a time. Then you put the book down, think about it, and walk away for a while.

I am probably so struck at the moment because, as I write, I’m in the heart of Rome in an area where I lived for many years. It occurred to me that I spent more years here, than I did in my native place before I moved away. In a sense, I am there, to where I tend. I am alive here in a way that I am not when I go back to my present locale. Perhaps I hang my hat there, but its real hook is here. That’s what Esolen is on to.

Do not hesitate. Just order it. It is available for PRE-ORDER at a 24% discount at the time of this writing. There is a KINDLE version, too.

Nostalgia: Going Home in a Homeless World by Anthony Esolen

This isn’t an overtly Catholic book, but it is deeply Catholic in its worldview.

While Esolen uses little in the way of overtly churchy material, he – consciously or unconsciously – provides an argument for what I’ve been talking about for many years now: the revitalization of our Catholic identity, especially through a restoration of our sacred liturgical worship.

How often is the charge of “nostalgia” flung as a cliché into the teeth of those who desire, with their legitimate aspirations, the liturgical forms of their forebears?

Nostalgia, however, is, as the Greek indicates, a pain (algea) we feel for our “return home” (nostron): “pain for the return, ache for the homecoming.” It is an essential longing.

False nostalgia might be thought of as a desire for some “golden age” that is no more, and probably never was. A desire for something better. Augustine, drawing on the science of the day, describes the heart as restless because, according to ancient thought, gravity was a tendency within the thing itself which compelled it to go to where it belonged. The object tries to get where it is supposed to be. Thus, with the heart and God. Augustine says, “amor meus, pondus meum… my love is my weight”.

This is at the heart of what Esolen explores in Nostalgia.

He opens the book with Odysseus, sitting by the sea on Calypso’s island. He pines for Ithaca, for home, not because it is better than this enthralling captivity, but because, simply put, Ithaca is his home and this dreamy place isn’t. Everything with Calypso might be “better”, but it isn’t where he is supposed to be.

The small and even poor house in a humble neighborhood might not compare to the far more splendid starter-castle which through sweat and ingenuity you’ve worked up to, but it won’t be the same thing as what that old home was. And Esolen is not saying that nostalgia is nailed to a place and time. After all, God told Abraham to leave the place of his fathers and go to a new land, which would become the new place for new fathers. Of course, God can do that sort of thing, and even change your name, and make it right.

With every page, I cannot help but find a parallel with the devastation to our Catholic identity caused over the last decades, especially through devastation of our sacred liturgical worship. We are our rites. Change and tinker and make “progress with our rites” and you alter our identity as Catholics. The damage has been nearly catastrophic.

Esolen ranges all over, from the Odyssey to Shakespeare to Thomas Wolfe to Hilaire Beloc. Thank you, Professor, also for providing an INDEX! He draws on a short story by Flannery O’Connor about a “progressive” who, hating his own family, sells off parcels of their property for the sake of “progress”, like building a gas station that would blot their view of the woods. “Progress here,” writes Esolen, “is not the destruction of beauty. There is no great beauty. It is the destruction of a place”.

How’s that “springtime” of the Church thing going?

How the tinkerers and snipper pasters of the Novus Ordo got it wrong.

Those technocrats, for the sake of progress, damaged not something that was technically perfect, every bit accounted for somehow and having a utilitarian purpose to justify its continuance in our rites. They damaged our place, our home, our patria, where we start from and toward which we tend.

No wonder we are so damn screwed up as a Church.

Today I have read about such a (seemingly) important moment as a Synod of Bishops being run by – and I note the full irony in what I am about to write – not our Anthony Blanches, but by our Hoopers. By Hoopers with Anthony’s affliction but with none of his substance.

Many of you have been misunderstood and mistreated for your desire to go home, to be a Roman in the Roman thing, your rite, your patria which you ache for because it is yours. I sure have my stripes to show for it and the long tracks of my tears.

Time after time I have spoken with people, especially with priests, who at some point woke up from Calypso’s arms, who opened their eyes within the sty far from home, and realized that they had both squandered the patrimony they had or had been cheated out of the patrimony they didn’t know that they ought to have been given.

In his introduction, Esolen ends one section with the reaction of the progressive to those who feel deeply their sense of belonging, their desire to be placed and rooted.

“[P]eople who object to nostalgia are afraid that their achievements, such as they are, will not stand scrutiny. “No, you don’t want to go home!” they cry. They must cry, they must make the noise they can, because if they cease for a moment, we hear the calls of sanity and sweetness again, and we may just shake our heads as if awaking from bad and feverish dream. Coming to ourselves, we may resolve, like the prodigal, to “arise and go to my father’s house.”

I’ll probably write more on Esolen’s book along the way.

Father I loved your Brideshead metaphor. I need to re-view the Jeremy Irons PBS series or re-listen to his narration of Waugh’s unabridged classic. Brideshead captures that nostalgia concept so well.

I do feel like we have a Church run by a bunch of half wit Hoopers suffering from all of Blanch’s self destructive appetites, but lacking his knowledge and culture.

Nostalgia is a word I use often, especially as the years fly by. I had a good dose of it this morning as the wonderful visiting priest said the Roman Canon! (Hope I have the correct terminology.) When it is prayed at Mass, one can feel the presence of each and every saint who is named. coming to worship the Lord with us. At least that’s my experience! I long for what we have lost, but I know I sound like a broken record. God bless you, FAther Z; wish I could visit all those places in Rome with you!

“Time after time I have spoken with people, especially with priests, who at some point woke up from Calypso’s arms, who opened their eyes in the sty far from home, and realized that they had both squandered the patrimony they had or had been cheated out of the patrimony they didn’t know that they ought to have been given.”

Beautifully said!

Father, as I am reading this, I am taken back to my thought about the neoliberal, technocratic damage inflicted to the world of work and to the relationship that a person has to the fruits of their work, indeed, of quasi-Marxian “alienation”, and a similar damage wrought on this neoliberal revolution on the world of academia, where everything has been ruthlessly subjected to the will of technocratic, managerial class and to the diktat of net profit over any other (and, specifically, ethical) consideration

I have a nostalgia for the world where employees are not merely “human resources” and where universities are not corporations ran by CEOs but places of learning and communities of students and scholars, like in the good, not so old days. The iron logic of “progress” trumps reason and ethics, with inexcusable complicity of our elites.

In the past 40, 50 years we have lost something in almost any area of human and social activity, starting with our worship, ending with more mundane, but also important aspects of our lives.

My childhood was that of a city kid with a daredevil attitude. My recklessness was kept in check by Sisters of Mercy, who reigned in stupid behavior. Also our pastor played football for Villanova in the 1920s, he frightened the bad behavior right out of us. All of this took place in the 1940s, and I never heard the word homosexual, and perverted men were no where to be found, in fact it wasn’t until my days in the service that I found out about all of that. My 8 years in that school played a large part in my future life, which led to some measure of success. As I look around now I suffer from a terrible bout of nostalgia.