This Sunday’s Collect for the Extraordinary Form survived the snipping and pasting of the Consilium and the late Annibale Bugnini’s liturgical experts to be used in the Ordinary Form on Tuesday of the 2nd week of Lent. Figure that one out.

This Sunday’s Collect for the Extraordinary Form survived the snipping and pasting of the Consilium and the late Annibale Bugnini’s liturgical experts to be used in the Ordinary Form on Tuesday of the 2nd week of Lent. Figure that one out.

Custodi, Domine, quaesumus, Ecclesiam tuam propitiatione perpetua: et quia sine te labitur humana mortalitas; tuis semper auxiliis et abstrahatur a noxiis, et ad salutaria dirigatur.

Propitiatio, in its fundamental meaning, is “an appeasing, atonement, propitiation”. The dictionary of liturgical Latin Blaise/Dumas also gives us a view of the word as “favor”. This makes sense. God has been appeased and rendered favorable again towards us sinners by the propitiatory actions Christ fulfilled on the Cross. We have renewed these through the centuries in Holy Mass.

Mortalitas refers, as you might guess, to the fact that we die, our mortality. Inherent in the word is the concept that we die in our flesh. So, you ought also to hear “flesh” when you hear mortalitas.

Labitur is from labor. This is not the substantive labor but the verb, labor, lapsus. It means, “to glide, fall, to move gently along a smooth surface, to fall, slide”.

Auxilium, in the plural, has a military overtone. There is also a medical undertone too, “an antidote, remedy, in the most extended sense of the word”. Pair this up with noxius, a, um, which points at things which are injurious or harmful. There is a moral element as well or “a fault, offence, trespass”.

Salutaria is the plural of neuter salutare which looks like an infinitive but isn’t. Our constant companion the Lewis & Short Dictionary says the neuter substantive salutare is “salvation, deliverance, health” in later Latin. The adjectival form, salutaris, is “of or belonging to well-being, healthful, wholesome”. Think of English “salutary” and O salutaris hostia in the Eucharistic hymn by St. Thomas Aquinas (+1274).

When this word is in the neuter plural (salutaria) there is a phrase in Latin bibere salutaria alicui … to drink one’s health” or literally “to drink healths to someone”. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet during the famous “Queen Mab” speech Mercutio declares that a soldier dreams, inter alia, of “healths five fathom deep,” (I, iv) and in Henry VIII the King says to Cardinal Wolsey, “I have half a dozen healths to drink to these” (I, iv).

Wine and health are closely related in the ancient world. In the parable of the Good Samaritan the good passerby pours oil and wine into the wounds of the man who was assaulted (Luke 10:25-37). St. Paul wrote to St. Timothy:

“No longer drink only water, but take a little wine for the sake of your stomach and your frequent ailments” (1 Tim 5:23).

Apart from its resemblance to blood, it is no surprise that Christ should choose this healthful daily staple as the matter of our saving Sacrament.

Wine was often safer to drink than water in the ancient world, though it was nearly always mixed with water to some extent. To drink uncut wine, merum in Latin (from the adjective merus “unadulterated”, giving us the English word “mere”) was considered barbaric. Cicero (+43 BC) and others hurled that accusation at Marcus Antonius (+31 BC) who was a renowned merum swiller.

Catholics sing the word merum in the hymn of the Holy Thursday liturgy, Pange lingua gloriosi, by St. Thomas Aquinas: “fitque sanguis Christi merum… and the (uncut) wine becomes the Blood of Christ”. In sacramental terms, there is a link between wine and health in the sense of salvation. During Holy Mass, we offer gifts of wine with water to become our spiritual “healths” once it is changed into the Blood of Christ. These archaic and literary references help us drill into the language of our prayers.

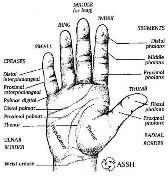

Let’s drill some more. Did you know that the index finger was called digitus salutaris, and that the ancient Romans held it up when greeting people? We don’t do that very often these days. I believe modern usage, at least on roadways, more commonly employs a different finger.

The special designations of fingers in Latin are pollex (thumb); index or salutaris (forefinger); medius, infamis or impudicus (middle finger); minimo proximus or medicinalis (ring finger); minimus (little finger, “pinky”). The priest, during Mass in the Vetus Ordo, always holds the consecrated Host only between his thumb and the digitus salutaris. One way to harm a priest, our mediator at the altar and in the confessional, was to chop off his index fingers. This was done to the North American martyrs and missionaries. Priests without those fingers were forbidden to say Mass without special permission from the Holy See. Those significance of those fingers was clearly understood by those who hate the Church, priesthood, and the Eucharist as being especially important. Even the thumb can play a kind of mystical priestly role in the Mass. During Mass when the priest has his hands together, he places his right thumb over his left to form a cross. This is deliberate in the Roman Rite, and it is indicated as such in the Ritus Servandus at the beginning of the Missal.

III De initio Missae

Sacerdos cum primum descenderit sub infimum gradum altaris, convertit se ad ipsum altare, ubi stans in medio, iunctis manibus ante pectus, extensis et iunctis pariter digitis, et pollice dextero super sinistrum posito in modum crucis (quod semper servatur quando iunguntur manus, praeterquam post Consecrationem), detecto capite, facta prius Cruci vel altari profunda reverentia, vel si in eo sit tabernaculum sanctissimi Sacramenti, facta genuflexione, erectus incipit Missam.

III. The Beginning of Mass

1. When the priest has descended to the lowest level of the Altar, he turns toward the Altar, and standing in the middle, with his hands joined before his breast with fingers extended and together, and with his right thumb over his left in the form of a cross (which form is always to be observed when joining the hands until after the Consecration), and with his head uncovered, having first reverenced the Crucifix or Altar, or if a Tabernacle containing the Blessed Sacrament is on the Altar, having genuflected, standing erect, he begins the Mass.

The Vetus Ordo is replete with details that bring great richness to our full, conscious and actual participation. Just sayin’.

And if you are wondering. No. It isn’t.

Let’s push this a little more.

The adjective medicinalis, “medicinal, healing”, comes from the verb medeor or medico, the original meaning of which has to do with “to heal” by magic. The verb traces back to the stem med– or “middle”. So, medicus, “doctor” is associated with “mediator”. We can think of this in terms of the English word “medium”, who is a mediator with the spirit world. The Latin poet Silius Italicus (Tiberius Catius Asconius Silius Italicus +101) called a magician “medicus vulgus” (Punica, III, 300). The ancients saw what we call the “ring finger” as having magical powers. This is reflected in the name digitus medicinalis, the “medicinal/magic” finger.

One of the most important Patristic Christological images in the ancient Church is Christus Medicus, the “Physician”. St. Augustine does amazing things with this image, and Christus Mediator. He is the doctor of the ailing soul. He is the only mediator between God and man.

LITERAL RENDERING:

Guard your Church, we beseech You, O Lord, with perpetual favor, and since without You our mortal flesh slides toward ruin by means of your helping remedies let it be pulled back from injuries and be guided unto saving healths.

Watch how the old incarnation of ICEL ruined the imagery.

OBSOLETE ICEL (1973):

Lord, watch over your Church,

and guide it with your unfailing love.

Protect us from what could harm us

and lead us to what will save us.

Help us always, for without you we are bound to fail.

We won’t ever have to hear that one again!

CURRENT ICEL (2011):

Guard your Church, we pray, O Lord, in your unceasing mercy,

and, since without you mortal humanity is sure to fall,

may we be kept by your constant helps from all harm

and directed to all that brings salvation.

We all know the image of the slippery slope. Once you are on this slope, scrabble and scratch with your weak hands as you can, and you can’t get a purchase.

You slide and slide, faster and faster. Down.

Our fallen nature and our habitual sins drag us onto the slope from which we cannot save ourselves.

In the sacraments and teachings of Holy Church, Christ extends the fingers of His saving hand.

He draws us back from a deadly slide with His Almighty hand.

“Propitiatio” invariably reminds me of the “propitiatorium” in the Vulgate, the Latin rendering of the “Mercy Seat.” Calls to mind gilt angels, incense, spattered blood, and absolution.

“Facies et propitiatorium de auro mundissimo” (Ex. 25:17)

The Septuagint has “hilasterion,” which means “that which procures propitiation or expiation. It is derived from “”hilaskomai,” meaning “to propitate or conciliate” or “have mercy upon.” This is the verb used in Luke 18:13: “hilastheti moi to hamartolo,” ie. “have mercy on me, a sinner.”

In Hebrew the word is “caforet,” and lexicon entry is, in a rather silly turn, “lid of the Ark.” At least they acknowledge that it’s derived from the root “cfr,”which is both “to cover” (like a lid) and “to make atonement or expiation for sin.” The old translators most certainly knew this. Hey look the ancients were smarter than the modern day Germans again…

Thank You Fr. Z.

I learned so much from that article. Never to old to learn.The old gray cells are still working as Hercule Poirot would say.

It got me thinking about the Novus Ordo, what do the Priest do in the Novus Ordo? I have watched them among all the noise and they just sit on a chair in the back or on the side while women do everything until the Consecration. What are the Rubics or do I really want to know?