The Laudator, whom I check often – I add some of his pithier quotes to my commonplace book – has a fascinating entry with descriptions of the Triumph given to Marcantonio Colonna after his victory at Lepanto. It makes for great reading.

Maracant… where I have heard that name recently?

The first description is from a spiffy book which I have recommended for years about the painter Caravaggio. Langdon treats well the spirituality underlying his work:

Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), p. 9: [US HERE – UK HERE]

Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), p. 9: [US HERE – UK HERE]

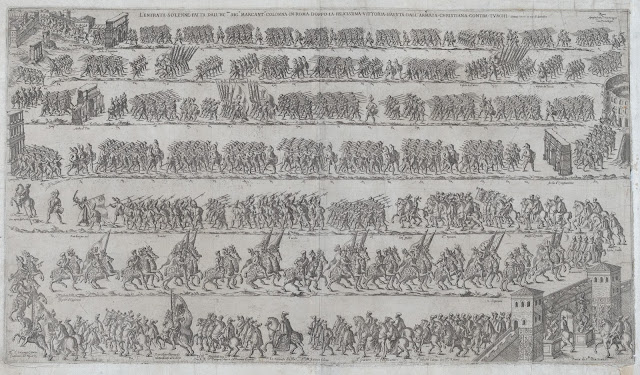

On 4 December 1571 an enormous theatrical triumph was staged in Rome. Its hero was Marcantonio Colonna, scion of one of the most illustrious of all Roman families, and commander of the papal galleys in the triumph of the Holy League over the Turks at Lepanto. He progressed from the church of San Sebastiano, on the Appian Way, passing the Baths of Caracalla, and under the triumphal arches of Constantine and Titus, to the monastery of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, built on the holiest site of the Capitol, at the very centre of the old Roman Empire.

Colonna rode, unarmed, on a white horse. He was escorted by a glittering cortège of five thousand people, and 170 liveried and chained Turkish prisoners were driven before him. Before them the standard of the sultan was trailed in the dust. The procession pressed forward through tumultuous applause. ‘Here from every part’, wrote an observer, ‘his name rang out. Everyone rushed to the street, clapping their hands. Crowds of people thronged together, crying out, while trumpets serenaded him. He was greeted from far and near, by people gesturing, shouting, waving caps and banner’. Ringed by twenty-five Cardinals, Colonna crossed the Tiber at the Ponte Sant’ Angelo, and then rode to St Peter’s and the Vatican Palace, where Pope Pius V received him in the Sala Regia.

His progress was modelled on the triumphs that were granted to generals in ancient Rome and it drew on the splendour of ancient myth. Yet it was also an intensely Christian event. The façade of the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli was decorated with captured Turkish flags. It bore the proud inscription: `The gratitude which, in their pagan folly, the Ancients offered to their idols, the Christian conqueror, who ascends the Aracoeli, now gives, with pious devotion, to the true God, to Christ the Redeemer, and to His most glorious Mother’. Colonna seemed to bring the new promise of a more joyful Christian era.

Francesco Tramezzino, L’entrata solenne fatta dall’ecmo. Sigr. Marcantono Colonna in Roma doppo la felicissima vittoria havuta dall’armata Christiana contra Turchi (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession number 47.105.10). Click to enlarge.

Ludwig Pastor (1854-1928), The History of the Popes, Vol. XVIII, tr. Ralph Francis Kerr (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1929), pp. 431-433 (footnotes omitted):

All Rome was in a stir when the bright and sunny day of December 4th dawned. Thousands of people had gathered along the Via Appia, where, near the basilica of St. Sebastian, Girolamo Bonelli and the Swiss Guard, the Senator and the Conservatori, awaited the arrival of Colonna, who was to come from Marino. Unarmed, and with no decoration but the Golden Fleece, Marcantonio rode upon a white horse given him by the Pope; a black silk mantle lined with fur covered his tunic of cloth of gold, and on his head he wore a black velvet cap, with a white plume fastened with a pearl clasp.

Amid scenes of extraordinary rejoicing, the clash of trumpets, and the firing of guns, the cortège was formed, in which were to be seen the gaily coloured banners of all the city corporations, and the 13 Rioni of Rome. As can easily be understood, the chief interest was excited by the 170 Turkish prisoners, dressed in red and yellow, in chains, and guarded by halbardiers. In front of them rode a Roman in Turkish dress dragging the standard of the sultan in the dust. At the side of the prisoners walked a hermit, who had taken part in the battle, and whom the people, by whom he was greatly loved, called Fate bene per voi, from the words which he was always saying. The standard of the Church was borne by Romegasso, and that of the city of Rome by Giovan Giorgio Cesarini, with whom rode Pompeo Colonna and Onorato Caetani, and the two nephews of the Pope, Michele and Girolamo Bonelli; then came Marcantonio Colonna, who was rapturously acclaimed by all, and was followed by the Senator of Rome and the Conservatori, and a large number of his friends and comrades. The Papal light cavalry brought the procession to an end.

As Charles V. had done 35 years before, so Marcantonio Colonna, entering the city by the Porta S. Sebastiano, and passing the Baths of Caracalla, and under the triumphal arches of Constantine and Titus, chmbed the hill of the Capitol, and came to S. Marco, passing thence along the Via Papale to the Bridge of St. Angelo. On the way he came to the statue of Pasquino, which was gaily decorated; in the left hand was the head of a Turk, with blood pouring from the mouth, and in the right a drawn sword. [Pasquino is still there!]

After praying in St. Peter’s at the tomb of the Prince of the Apostles, and offering, in allusion to his own name, a column of silver, Colonna proceeded to the Vatican, where the Pope received him, accompanied by 25 Cardinals, with the greatest honour. He exhorted the victor of Lepanto to give the glory to God, Who, despite our sins, had been so kind and merciful.

The distance between planet earth and the sun seems shorter than the distance between the men in Rome of that time and the specimens we have now.

Kathleen10

Yes, indeed. In those days, when a speech was given in public on the occasion of such a celebration, they still used Latin: which, I presume, was understood, if not by all, certainly by good many of the participants, above all by all the ecclesiastics, at least by those of the higher ranks, but also most likely by most of the educated people present. The style was elegant, as can be seen right from the opening paragraph (there is no need to translate it: basically, its a bunch of “captatio benevolentiae”):

Ex Oratione in reditu ad Urbem Marci Antonii Columnae, post Turcas navali proelio victos, anno MDLXXI:

Si ulla post hominum memoriam parta victoria est, in qua et admirabilis se divini numinis potentia ostenderit, et quid fortium virorum virtus, quid singularis ductorum prudentia valeat, cognitum ac declaratum sit: in hac certe, quam superioribus diebus imperatores ac milites nostri ex immanissimo ac teterrimo Christiani nominis hoste retulerunt, ita haec omnia patefacta sunt, ut numquam majoribus aut illustrioribus argumentis aut illustrata esse aut in posterum illustrari posse videantur. Quare et immortali ac praepotenti Deo, huius tanti boni, ut aliorum omnium, auctori, gratiae, quantas maximas animus noster capit, agendae sunt. Et fortissimis ac clarissimis viris, qui periculum a nobis omnibus vitae suae periculo depulerunt, qui barbaris in nos irruentibus iter corporibus suis occluserunt, qui pestem ac perniciem, quam illi nobis machinabantur, in ipsorum capita converterunt, qui illorum temeritatem consilio, furorem fortitudine, audaciam virtute superarunt, novi atque inusitati honores pro nova ipsorum atque inusitata virtute tribuendi. Quod enim tantum ac tam singulare honoris genus reperiri aut excogitari potest, quod non et in aliis, qui egregiam in hoc bello reipublicae Christianae operam navarunt, et tuae inprimis, M. Antoni Columna, virtuti rebusque gestis, et ab aliis Christianis populis et praecipue a Populo Romano debeatur?

[Great quote.]