Sunrise, when? 05:54

Sunrise, when? 05:54

Sunset, when? 19:36

Ave Maria? 19:00

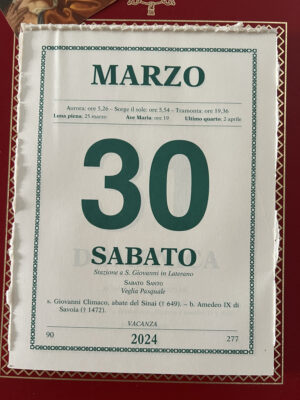

Quiet day, as befitting Holy Saturday. All is quiet in the Church as Christ’s soon to be reclaimed Body is in the tomb while His human fused divinity harrows Hell.

HEY! a*****.w****@erickson.com My email to you got kicked back!

Starting with some citations in the New Testament we started to pry open what came to be known as the “harrowing” or “raid” of hell, what Christ did between His death on the Cross and His resurrection.

Originally, the English word “harrow” has to do with preparing ground for tilling. “Harrowing” involved drawing a kind of grate with downward spikes over the ground to break it up. Here’s an image from a 16th c Book of Hours:

After the Council Trent was closed, the Roman Catechism was issued in 1566. It was intended especially to shore up the fundamental doctrine of the clergy and be an aid for pastoral preaching. I take my title for the columns I post at One Peter Five from Trent, which says that sermons should be giving “at least on Sundays”. The Catechism explains with characteristic clarity the articles of the Apostle’s Creed and therefore what the “harrowing of hell” was and why Christ did it. The Roman Catechism states that after His death Christ’s soul, in no way diminished, descended into hell in solidarity with man not to suffer, but to “liberate the holy and the just from their painful captivity, and to impart to them the fruit of His Passion.” The Catechism then says, “Having explained these things, the pastor should next proceed to teach that …”, and here let me fulfill the Catechism’s directive,

Christ the Lord descended into hell, in order that having despoiled the demons, He might liberate from prison those holy Fathers and the other just souls, and might bring them into heaven with Himself. This He accomplished in an admirable and most glorious manner; for His august presence at once shed a celestial lustre upon the captives and filled them with inconceivable joy and delight. He also imparted to them that supreme happiness which consists in the vision of God, thus verifying His promise to the thief on the cross: This day thou shalt be with me in paradise. […] But the better to understand the efficacy of this mystery we should frequently call to mind that not only the just who were born after the coming of our Lord, but also those who preceded Him from the days of Adam, or who shall be born until the end of time, obtain their salvation through the benefit of His Passion. Wherefore before His death and Resurrection heaven was closed against every child of Adam. The souls of the just, on their departure from this life, were either borne to the bosom of Abraham; or, as is still the case with those who have something to be washed away or satisfied for, were purified in the fire of purgatory.

That sure reference work for the Catholic faith issued in 1997 in the Latin typical edition (1994 in French), the Catechism of the Catholic Church, covers this article of the Creed in par. 632ff. The first meaning applied to this phrase was that “Jesus, like all men, experienced death and in his soul joined the others in the realm of the dead. But he descended there as Savior, proclaiming the Good News to the spirits imprisoned there” (632). The place Christ went, the abode of the dead, biblical sheol, is where the none of the dead can see God, regardless of their wickedness or righteousness. Christ descended into sheol to liberate the righteous dead, not the damned. Thus, the “the Author of life”, by dying destroyed “him who has the power of death, that is, the devil” (635). Furthermore, as we read in an ancient Holy Saturday sermon in Greek (included in the Office of Readings of the Liturgy of the Hours),

He has gone to search for Adam, our first father, as for a lost sheep. Greatly desiring to visit those who live in darkness and in the shadow of death, He has gone to free from sorrow Adam in his bonds and Eve, captive with him – He who is both their God and the son of Eve.

This article of the Creed underscores Christ as the Second Adam, making right the damage worked by the First Adam in the original sin of our first parents.

It may be that element of ancient mythologies influenced the telling of this doctrine of the Apostolic Church. Down through the centuries this idea of the “harrowing of hell” fueled the imagination of Christians and their theological reflection resulting in apocryphal “gospel” accounts, medieval mystery plays, and works of art such as Eastern icons. There is something paradoxical in the core of the doctrine, namely, that our God, in an indestructible bond with our humanity, might go to hell, even if for a brief and specific mission.

In early Christian apocrypha, such as the Greek fourth century Acts of Pilate or the Latin medieval Gospel of Nicodemus there were imagined dialogues between the King of Glory, Christ, and the Prince of Hades, Satan. In the medieval period, particularly from 13-16th century England, there were performances of mystery plays, including of course the dramatic “harrowing of hell”. Mystery plays were an important force in the revival of modern theatre. The 13th century Aurea Legenda or Golden Legend compiled by Jacob de Voragine (+1298) includes the tale. Dante in the Divine Comedy has Virgil give the poet an eyewitness account (Inf 4,52-63).

In Eastern iconic depictions of the mystery, you see the risen Lord in luminous garb, carrying a Cross, trampling broken doors. He extends His hand, sometimes to an old man, Adam, or to others below in a cave or tomb-like grotto. Sometimes we see Dismas, the Good Thief, to whom Christ promised salvation that very day as they were crucified together. In renaissance frescoes and paintings the same themes continue, but often with the dramatic addition of irritated devil onlookers, probably echoes in paint of the mystery plays common to the era.

Through the ages up to our own day in the Easter vigil liturgy in the Eastern Churches, Catholic and Orthodox, a sermon known simply as “The Easter Sermon” attributed to St. john Chrysostom (+407) is read, often with dialogue-like participation of the congregation (not “assembly”). Here is an excerpt:

Let no one fear death, for the Death of our Savior has set us free.

He has destroyed it by enduring it

He destroyed Hades when He descended into it

He put it into an uproar even as it tasted of His flesh

Isaiah foretold this when he said

“You, O Hell, have been troubled by encountering Him below.

Hell was in an uproar because it was done away with

It was in an uproar because it is mocked.

It was in an uproar, for it is destroyed

It is in an uproar, for it is annihilated

It is in an uproar, for it is now made captive.

Hell took a body, and discovered God.

It took earth, and encountered Heaven.

It took what it saw, and was overcome by what it did not see.

O death, where is thy sting?

O Hades, where is thy victory?

The “harrowing of hell”, however it took place and however it may be depicted, is an doctrine of faith to which as Christians we give assent. The central point of this article of the Creed is that the Christ in His atoning Sacrifice has free us from the eternal bonds of death in sin, liberated us from the fear of unavoidable everlasting separation from God.

Whether in our recitation of the Holy Rosary or during Holy Mass, every time you say “he descended to the dead” and in the newer version is “he descended into hell”, do so with hope in your heart and firm belief that Christ’s Sacrifice freed you from the inevitability of hell.

Alas this photo didn’t go so well since it focused on the screen. However, these were about to become lunch.

Fit for a Holy Saturday.

The priests are ready for Good Friday. So… I’m out of synch a little. I’ve been busy.

“Descendit ad inferos” is indeed ambiguous. Or rather, the Latin compasses both meanings, “unto the dead,” and “into hell”

I would argue, however, that this ambiguity can be resolved by having reference to the recieved Greek version of the text, which is sitting is some of our medieval manuscripts. The original text of the Apostles’ Creed, as far as we know, is Latin, but our forebearers definitely had a better understanding of Latin than we do. This official Greek version reads “eis ta katotata,” “unto the deepest regions.” The meaning of “katotata” seems, from my delving into the Bauer-Arndt-Gingrich, to only apply to the region.