From a reader…

From a reader…

What are the Four Catholic Creeds, and why don’t we use the most recent one in Mass?

Good question. Let’s start with some basics, which many readers might not know.

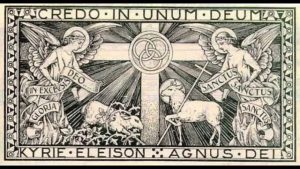

Our English word “creed” is from Old English creda, in turn from Latin credo, “I entrust, I believe”. The profession of faith we make during Holy Mass takes its nickname “Creed” from its first word in the Latin text which begins “Credo in unum Deum… I believe in one God…”. “Creed” is also used more generically for some statement of belief.

In the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, we recite the Creed mainly on Sundays and solemnities. In the traditional Extraordinary Form the Creed is used with much greater frequency.

Why do we have a Creed at Mass? Among other explanations we can turn to what the General Instruction of the Roman Missal says (67):

The purpose of the Symbolum or Profession of Faith, or Creed, is that the whole gathered people may respond to the word of God proclaimed in the readings taken from Sacred Scripture and explained in the homily and that they may also call to mind and confess the great mysteries of the faith by reciting the rule of faith in a formula approved for liturgical use, before these mysteries are celebrated in the Eucharist.

The 2002 Missale Romanum has some rubrics for the Creed. We read in the new translation of the Order of Mass at rubric 18: “At the end of the homily, the Symbol or Profession of Faith or Creed, when prescribed, is sung or said:…”. Oddly, the new translation excludes another rubric found in the Latin edition immediately after the Gregorian chant notation for how the priest is to sing the introduction, or intone, the Creed: “Toni integri in Graduali romano inveniuntur…. Complete tones are found in the Graduale Romanum.” The Graduale Romanum is published for the Holy See by the monks at the French Benedictine monastery at Solesmes. It contains all the chants needed for a choir, schola or congregation to sing the Proper and Ordinary in Latin.

Let no one claim congregations cannot sing the Creed in Latin! It is a powerful experience to hear a congregation sing the Creed with confidence. It isn’t hard. It just takes a little time and prompting. People should also be allowed actively and consciously to listen to beautiful settings from our treasury of sacred music.

For the Novus Ordo, or Ordinary Form, of Holy Mass – since the 2002 edition of the Missale Romanum – we are given two main options for the Profession of Faith. We may use the “Apostles Creed” or the “Nicean Creed” (fuller title “Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed”). Rubric 19 says that the Apostles Creed “adhiberi potest … can be used” in the place of the Nicene Creed “praesertim… especially” during Lent and the Easter season. That said, it is clearly the Church’s intention that Nicene Creed, which historically has been the only Creed for Mass, is the norm.

The Apostles Creed, or Symbolum Apostolicum, is especially familiar to those who recite the Holy Rosary. It is also used by other Christians, who accept it because it is not elaborate in its doctrinal scope. Many Christians are not interested in systematic doctrine.

In the early Church it was assumed that the Apostles themselves composed and handed down a “rule of faith”. There is pious legend of very ancient origin that the Apostles Creed was composed by the Twelve under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, each one of them contributing one of its “articles”. It is possible with some jostling and nudging to break down the Apostles Creed into twelve sections, though St. Thomas Aquinas (+1274) preferred to break it into seven (cf. STh II, q. 2). J.N.D. Kelly’s book Early Christian Creeds [US HERE – UK HERE] has great detail about this and other early professions of faith.

In the early Church it was assumed that the Apostles themselves composed and handed down a “rule of faith”. There is pious legend of very ancient origin that the Apostles Creed was composed by the Twelve under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, each one of them contributing one of its “articles”. It is possible with some jostling and nudging to break down the Apostles Creed into twelve sections, though St. Thomas Aquinas (+1274) preferred to break it into seven (cf. STh II, q. 2). J.N.D. Kelly’s book Early Christian Creeds [US HERE – UK HERE] has great detail about this and other early professions of faith.

Rufinus of Aquileia (+410), the old friend and sometime nemesis of the irascible St. Jerome (+420), in his Commentary on the Apostles Creed relates the story of this Creed’s origin, already old in his day. The Apostles, given the ability to speak many languages by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, were about to take leave of each other and go out into the world. They wanted a norm for preaching so that, even though they were very far apart from each other, they would still be unified in their teaching. “So, they met together in one spot and, being filled with the Holy Spirit, compiled this brief token … each making the contribution he thought fit; and they decreed that it should be handed out as standard teaching to believers.” There is a contemporary document from Northern Italy, probably based on notes from the preaching of St. Ambrose of Milan (+397), that the Twelve were worried about heresy and they wanted to strengthen bishops who succeeded them. A sermon incorrectly attributed to St. Augustine of Hippo even breaks down which Apostle contributed which article and says this took place on the tenth day after the Ascension. When the Holy Spirit came they were all “inflamed like red-hot iron”. Peter started, of course, followed by Andrew, etc.

The Apostles Creed is much shorter than the Nicene Creed because in its earliest forms it predates the controversies about the divinity of the Holy Spirit and of Christ and His two natures, divine and human.

There was an even shorter and more ancient forerunner of the Apostles Creed called the Old Roman Creed or Old Roman Symbol, based in turn on a 2nd century regula fidei or “rule of faith” used in questioning candidates before baptism. St. Ambrose mentions an “Apostles Creed” in letter 42 to Pope Siricius. This could have been that Old Roman Creed or some subsequent development. The first full quotation of the Apostles Creed comes in an 8th century work by the St. Priminius (+753). After Charlemagne spread it through his lands it would eventually be used in Rome itself.

Thus in the Apostles Creed we have a profession of faith of very ancient origin, certainly going back to the very early times of the Church. This venerable collection of statements of belief epitomizes the most ancient declarations of faith of our forebears. Each point is rooted in the New Testament and the most deeply held convictions of the earliest Christians.

Here we must pause to look a the term “Symbol”, used to describe a “profession of faith” or a “creed”. The word comes from the Greek, a compound of the verb ballein (“throw”) and the preposition syn (“together). A symbolon was a token of proof, that something was genuine or that a person was who he said he was. For example, a symbolon could be the impression carved into something or left in a waxen seal (Greek character – as in the indelible change that takes place in the soul when you are baptized, confirmed or ordained.). Think of a modern silver stamp or the shiny holographic stamps on modern sports memorabilia and money.

A symbolon could also be half of an object purposely broken in half so that, once matched with its other half, it became a sign, a “symbol” of the identity of the one who carried it. An ancient contract, for example, might be written on a clay tablet, baked, and then broken in half, so that the two parties each had a piece that would fit together. Shards of pottery called “tallies” were also used, as in the story told by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus about Glaucus the Spartan and the man from Miletus and their financial deal.

In sum, in a “symbol” you “throw” the parts “together” to ensure identity. This has become a common topos in literature. Later cut pieces of paper could be used. In interior identity was exteriorized with a material symbol. A symbolon could also be used as a “ticket” for voting or even for travelling. The ever-sarcastic Tertullian (+ c. 220) used it in this sense when attacking the heretic Marcion, asking by what symbolum he took St. Paul “on board” his ship. St. Cyprian of Carthage (+258) applies the word to an early profession of faith much like the Apostles Creed.

In John LeCarre’s spy-novel Smiley’s People a torn postcard is used as a token to prove identity. In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night Sebastian and Viola find they are twins this way. In the fluff movie The Parent Trap the identity of twins is discovered by halves of the same family photo. In the unfluffy history of the Franks, King Childeric, deposed as a libertine and debaucher, flees to Thuringia after leaving half of a gold coin with a friend so he could prove himself on his return. In Plato’s Symposium Aristophanes describes how Zeus split the originally androgynous into male and female halves who feel complete when they find each other in love. In the so-called “Judgment of Solomon” the identity of a baby is discovered by the threat of literal halving. None of this has anything to do with the Creed, of course, but it fun.

It is time to move on to the normative Creed used during Holy Mass. For the purposes of practicality, we must leave aside a separate option for the creedal variation of our renewal of baptismal vows with its dialogical structure.

The fuller title of the Creed we call by shorthand the “Nicene Creed” is the “Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed” (Symbolum Nicenum-Constantinopolitanum). The text has its roots in much earlier creeds and the questions and answers during baptismal rites going back close to Apostolic times. The text of our Mass’s Nicene Creed is related more immediately to the anti-Arian Council called by the Emperor Constantine at Nicea (in 325 in present-day Turkey).

Before the Council of Nicea creeds of various forms were for a local Church’s use. A new form of Creed developed from meetings of bishops in synods and councils held to address theological problems. The bishops and ecclesiastics who met in council had to subscribe to a summary of theological propositions which pointed to correct teaching, orthodoxy. They were tests.

Sometimes the formulas included anathemas for those who strayed from the faith they determined came from the Apostles: “As for those who say [HERESY X],… these the Catholic and apostolic Church anathematizes/kicks out.” The meaning of the Greek word anáthema drifted around considerably, by the way. It originally stood for something dedicated or set apart. It could be good, as in set apart for God. It came later to mean set apart in an evil way, apart or separate from the community.

In any event the Creed promulgated by the Council of Nicea was the first of its kind, in that it had a universal legal authority and its anathema excommunicated those who dissented from what it defined.

The Council of Nicea was called to help bring unity to the important social force of Christianity which had recently been legalized and then made the religion of the Empire.

The Council was directed to work through Christological questions (that is, theology about who Christ is) which were tearing apart the unity of the Church and thereby creating problems for society as a whole. What the Fathers of the Council needed to agree upon in some way, was the relation of Jesus Christ, the Son incarnate, to Almighty God the eternal Father. The Council also worked to fix a date for the celebration of Easter (the first Sunday after the first full moon following the Spring Equinox), and also issue laws for the discipline of church practices. The Council was about unity of faith and practice.

Regarding the Christological question, the Council Fathers defined what they determined to be the faith of the Church going back to the teachings of the Apostles regarding who Christ is: Christ is truly God in a literal way, with the same divinity as the Father, and not just in a metaphorical way.

A theological debate was gripping especially the Greek East, where a priest named Arius (+336) in Alexandria had stirred and intensified a long debated proposition that Christ, identified with the Son, was not of the same divine nature as the Father, but was rather the first, highest, most sublime of all creatures. Christ was in a way divine, but not in same way the Father is divine. In fact, the pre-Incarnate Son was a creature. In the famous phrase of the Arians, “there was a time when he was not”. That meant he wasn’t eternal and God as the Father was eternal and God.

The theological twists of terminology are extremely complicated, and I run the risk of gross oversimplifications in what follows.

The Arian question divided the ancient Church and Empire. The Council at Nicea condemned the Arian errors and determined that by Christian Faith we believe that the Son is homoousios, Greek for “of the same substance” or “of the same being”, with the Father. Greek ousia, a feminine participle of the verb einai, “to be”, is a tricky term basically meaning “being”. Ousia is rendered into Latin, and therefore English, in a bewildering number of ways depending on the topic and era. Ousia could be rendered in Latin as either substantia (substance) or essentia (essence). To make this even more confusing, the term homoousios itself was controversial because the word had been used by Gnostics in a way that was later condemned. But we must keep moving…. Homoousios is rendered in Latin as consubstantialis.

The brilliant but erratic Church wild-child Tertullian (+c.220) was the first Latin writer we know of to render homoousios into Latin as consubstantialis (Against Hermogenes 44).

Tertullian chose substantia probably because Latin lacks many verb forms that Greek has.

Substantia was taken to mean what ousia meant, the way to describe the nature of a thing whereby it is what it is, namely, that which doesn’t depend on something else to exist.

Since classical Latin active lacks a participle for the verb esse, “to be”, another solution had to be found: substantia, something “standing under”. So, ousia is what subsists in itself and doesn’t depend on anything else. Consubstantialis was deemed the best Latin could do for homoousios, meaning, of the “of the same being/substance”.

The terms being and substance have certainly drifted apart from each other in philosophy, in metaphysics, over the centuries. Even in the ancient world different groups talked past each other with different understandings of the same terms. That said, today being and substance aren’t really the same thing in English.

The controversial decision to translate Latin consubstantialis with the Latinate slavishly literal “consubstantial” rather than “one in being” (as the bad old ICEL translation had it) was certainly correct.

May I add that, in some ways, the Arian crisis has reemerged in a deadly new form? If those who say that people in the state of mortal sin can properly be admitted to Holy Communion, then the divinity of the Lord and the doctrine of transubstantiation are put into question. Do we believe what Christ said about divorce and remarriage? Was He wrong? If He was wrong, He isn’t God and what we do at Mass is idolatry.

The next part of the history of the Creed we say during Holy Mass goes back to the time of another great Council of the Church, Constantinople I (381).

Oddly, the first text we have of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (the orthodox Catholic faith proclaimed at Nicea as expressed and expanded by the Council Fathers at Constantinople to account for other heresies that had been dealt with during the intervening years) actually shows up in the acts of yet another Council, the Council of Chalcedon (451) during which the Fathers defined that Christ had two perfect natures, divine and human.

At sessions of Chalcedon, the Nicene Creed was publicly read along with “the faith of the 150 fathers”, that is, the Creed used during Council of Constantinople in 381. Amazingly the minutes of the Council of Chalcedon, its acta, all survived. That is how we have the text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed.

Furthermore, there enough differences between the original Nicene Creed and what we call the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed that we can say the later constitutes its own text. It is not merely a modification of the original Nicene version.

Perhaps that is enough about those ancient liturgical creeds.

There are other approved Creeds, not to be used at Mass, which deserve mention.

The so-called “Athanasian Creed”, called also Quicumque vult, was recited by clerics and religious occasionally in the pre-Conciliar form of the Office. Hence, it is also a liturgical creed, but not for Mass.

The Athanasian Creed was probably written in Latin in perhaps around the 6th century and got its name from a medieval legend that St. Athanasius (+373), during one of his exiles, gave the text to Pope Julius I (+352). It contains precise Trinitarian and Christological statements and ends with the less-than-ambiguous: “this is the Catholic Faith; which except a man believe truly and firmly, he cannot be saved.”

Another creed is the Creed of Pope Pius IV, called also the Professio Fidei Tridentina, issued on 13 November 13 1565 by Pope Pius IV in the Bull Iniunctum nobis after the Council of Trent (1545 – 1563). Hence, it was designed to defend the Catholic faith against Protestant error. This is one of the four authoritative Creeds of the Catholic Church. It was modified slightly after the First Vatican Council (1869 – 1870) to harmonize it with the dogmatic definitions of that Council. It was long used as an oath of loyalty for theologians and pastors, etc., and also for the reception of converts. This was the Creed my pastor had me recite when I was brought into the Church. It seems to have stuck.

I should mention also the non-liturgical “Credo of the People of God” promulgated in 1968 by Pope Paul VI for the 19th centenary of the martyrdom of Sts. Peter and Paul. In his Motu Proprio Solemni hac liturgia by which he promulgated this Creed, a clearly troubled Paul wrote about those days as if he were describing our own times:

In making this profession, we are aware of the disquiet which agitates certain modern quarters with regard to the faith. They do not escape the influence of a world being profoundly changed, in which so many certainties are being disputed or discussed. We see even Catholics allowing themselves to be seized by a kind of passion for change and novelty. The Church, most assuredly, has always the duty to carry on the effort to study more deeply and to present, in a manner ever better adapted to successive generations, the unfathomable mysteries of God, rich for all in fruits of salvation. But at the same time the greatest care must be taken, while fulfilling the indispensable duty of research, to do no injury to the teachings of Christian doctrine. For that would be to give rise, as is unfortunately seen in these days, to disturbance and perplexity in many faithful souls.

This describes Paul’s times, but our own as well, especially in light of how some people interpret Amoris laetitia.

The recitation of our Creeds, ancient and modern, brief or long, is necessary for us as Catholics.

It has been said that Creeds are for the head what good works are for the heart.

If we do not know the basics we believe as Christians, we cannot be good Catholics. We don’t know who we are.

We need to understand the basic tenets of our Faith and be able to stand up and make a profession of that Christian Faith when it is safe and convenient and when it is unpopular or even dangerous.

The repetition of the articles of faith, especially with others, can help to strengthen us in time of trial. This was certainly the case with the ancient martyrs. But no less is it the case in modern times.

For example, during the Chinese persecution of Christians at the end of the 19th century a 14 year old girl named Anna Wang was martyred in Hebei during the nationalistic Boxer Rebellion. With other Christians she was told to renounce Christ or die. Anna’s family fell, but she responded: “I believe in God. I am a Christian. I do not renounce God. Jesus save me!” She died and was born into heaven. Surely her opening declaration came from the Creed. We all face challenges to our faith, many of us on a daily basis. The recitation of creeds can be a preparation for our trials, small and large.

I hope these brief observations help.

A new form of Creed developed from meetings of bishops in synods and councils held to address theological problems.

Except what the Latin Church recites is NOT what was formulated at the Council. We really should address the filioque controversy and find a way to resolve it. The original formulation read “I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord, the giver of life,who proceedeth from the Father .” Many Orthodox would not oppose the addition of the Son provided that the translation was “through the Son” as opposed to “and the Son”

But the addition of this phrase outside of the Council parameters is problematic….and we see this same dynamic occurring after VII…must be something about the Romans/Latins….to paraphrase Hank Williams Jr. the Latin church is just “carrying on a family tradition!”

This blog entry, dear Father, is part of why I follow your blog.

Thank you for that wonderful catechesis, Father. And I was moved to look up Anna Wang, or Saint Anna Wang, as I learned. She consecrated herself to virginity from an early age, refusing a traditional marriage (which in China of that era must have taken some fortitude) and was martyred in a horrible way – hacked to death, it seems, even offering her arm to be cut off after other barbarities had been perpetrated on her. So like what we read of the first martyrs in Roman times, which are too often dissed as “pious fictions”.

Why does the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed omit the “Communion of Saints” of the the Apostles’ Creed?

Thank you Father for the great post.

Could any readers help me with this question.

In my archdiocese the Nicene Creed used in the Ordinary Form mass now omits the word ‘men’ in the following line, so that it now reads …

For us and for our salvation

instead of …

For us men and our salvation

Is that correct to omit ‘men’ or is that a local variation they just made up?

If you look at the Wikipedia entry:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicene_Creed#Original_Nicene_Creed_of_325

you will see that the original Greek versions, as well as the Latin version, use, “men”. It means, “men,” as in the representative of humanity, not the male species. People who omit men and use, “us,” are flouting tradition for the sake of inclusivity based, probably, on a poor understanding of the original languages. Even the Armenian version uses, “humanity,” which is a cognate for, anthrópous [anthropous], in the original Greek.

The Chicken

Why weren’t the two latest Creeds to be used in the Mass?

Also, what is the reason for existence of a non-liturgical but official Catholic Creed?

Quicumque vult should be recited at least one Sunday a year, though ideally 2 or 3, in Mass (perhaps exclude a homily on those days).

The modern creed is written badly, is sloppy in its use of language and fails to connect with what We believe.

The first line should emphasise that God created everything and everyone but just refers to heaven and earth. The next line “his only son our Lord” doesn’t hit the mark on the Holy Trinity. The next line conceived by the holy spirit born of the virgin Mary fails to express that Jesus came down from heaven and that the virgin Mary retained her virginity and then we instantly jump to suffered under Pontious Pilate without any reason as to why Jesus chose to suffer for us. The classic he descended to hell is complete nonsense.

On the third day, he rose again from the dead, again no reason to explain why and ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of God the Father Almighty from whence he will come to judge the living and the dead. (Again why does Jesus retain the authority to judge)

I believe in the holy spirit,

I believe in the holy catholic church,

I believe in the communion of the saints,

I believe in one baptism for the forgiveness of sin (it should be clear that this reverts to original sin, otherwise the sacrament of confession would not be necessary).

I believe in the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting.

@Christ_opher1 I object to your accusation, principally on account of the ancientness of the Apostles’ Creed. At more than a millennium old, it’s hardly modern, and nobody to my knowledge has raised objections to it until recently. If it were ‘broken’ so to speak, wouldn’t the Magisterium have been exercised to correct it?