I got a very interesting e-mail with a good question for discussion by you readers.

I wanted to ask you if you are aware of any work that has tried to examine the issue of liturgy and contemporary culture. I was in a wedding party this past weekend. I won’t go into the details, but it was painful. First, a 41 year old man shouldn’t have to be in wedding parties. [Amen to that, brother!] But none of the party really practices. And I sat their thinking about the recent assertions by Archb. Piero Marini that the Novus Ordo is more relevant to contemporary culture. Most liturgical (apologia) in the past 30-40 years have been either pro or con for certain ways of doing things, but I’m not aware of much work that attempts to see the liturgy from its relevancy to culture outside of the Church. Maybe the question is a non-starter. Certainly the liturgy is a gift. The early Christians received it and "did in remembrance". I get that. But then there is the unquestionable (?) influence of Latin/Roman prayer forms on the Christian liturgical practice (the way the priest holds his hands). So, non-Christian culture has influenced Christian orthopraxis, it would seem. Any thoughts on sources for my inquiries?

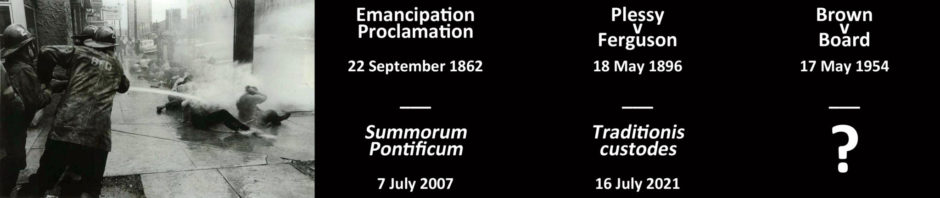

Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Summorum Pontificum was so important?

For a beginning, I think liturgy speaks with logical priority first and foremost ad intra. When it is faithfully executed, it also speaks ad extra. We all know stories of people who began their conversion, both intellectual and affective to the Church because of a liturgical experience. As a matter of fact, I would hazzard that the more rooted in the Catholic liturgical tradition the experience is, the more it tends to spark conversions.

In a sense, the impact of liturgy, because it is an encounter with Mysteryi, transcends issues of contemporary culture.

In a sense, the impact of liturgy, because it is an encounter with Mysteryi, transcends issues of contemporary culture.

At the same time, contemporary worldviews make it harder to latch onto the starting points.

Perhaps we could have some discussion of this and perhaps indications of sources.

I would begin by noting the book by The Heresy of Formlessness by M. Mosebach

The impact of liturgy on culture is one of the great points Josef Pieper makes in his Leisure, the Basis of Culture.

http://www.ignatius.com/Magazines/HPRweb/bk_pieper.htm

Dennis Quinn, who was one of the three professors at the IHP in Kansas, said it was this work by Pieper which made the biggest impact on him. From Quinn’s Program at a secular university there came around 200 conversions to the Catholic Faith. Some of them are monks in Clear Creek, Oklahoma. Talk about cultural impact.

The pagan Roman influence on Christian Latin liturgical prayers is indeed unquestioned. This is particularly true of the Roman Collects, where the second person (“Du-stil”) is used with a relative pronoun naming the god’s attributes and past good will to the person petitioning, and then an imperative requesting a present gift will appear. The “Deus qui…da nobis [often with ‘propitius’]” form was taken over virtually unaltered by early Christians. It is attested in too many pagan authors even to begin to exhaust, but cf. Horace “Odes” 1.10: “Mercuri,…/ qui feros cultus hominum recentum/voce formasti…”; Varro, “De Agricultura 134: “Iane pater,…preces precor ut sies volens propitius mihi liberisque meis…”; Virgil, “Aeneid” 3.85: “Da propriam, Thymbraee, domum; da moenia fessis.”

I do not know if this will help, but I frequent catholicculture.org and they had an article/essay on their site that talked about priestly narcissism and the Mass. It was about priests thinking too highly of themselves to change the Mass around.

http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=7918

An excellent source for the relationship of Catholicism to the “culture

of modernity” may be found in Tracey Rowland’s work, “Culture and the

Thomist Tradition: After Vatican II.”

Pertinent to the issue of liturgy is the “culture of deliberate forgetting,”

i.e., that the culture of modernity, which is virulently anti-Christian,

enforces forgetfulness as a solvent of Christian values and character

formation. A culture of deliberate forgetting is also deeply anti-virtue,

because virtue is possible only in so far as we understand ourselves as

beings in time, with a past that defines our characters.

Liturgy, particularly the TLM, rooted as it is in tradition, is a sort of

anti-solvent to cultural forgetfulness and, along with the Church calendar

of feasts and solemnities, serves to sanctify time. The TLM, then, may

serve as a cultural beacon of what modern culture has lost and can no longer

provide on its own.

The Holy Father said in his Regensburg address:

‘I must briefly refer to the third stage of dehellenization, which is now in progress. In the light of our experience with cultural pluralism, it is often said nowadays that the synthesis with Hellenism achieved in the early Church was an initial inculturation which ought not to be binding on other cultures. The latter are said to have the right to return to the simple message of the New Testament prior to that inculturation, in order to inculturate it anew in their own particular milieux. This thesis is not simply false, but it is coarse and lacking in precision. The New Testament was written in Greek and bears the imprint of the Greek spirit, which had already come to maturity as the Old Testament developed.’

Although it was said in a different context, I think it can be reasonably applied to the Latin Rite.

David Kubiak wrote:

“The pagan Roman influence on Christian Latin liturgical prayers is indeed unquestioned. This is particularly true of the Roman Collects, where the second person (“Du-stil”) is used with a relative pronoun naming the god’s attributes and past good will to the person petitioning, and then an imperative requesting a present gift will appear. The “Deus qui…da nobis [often with ‘propitius’]” form was taken over virtually unaltered by early Christians. It is attested in too many pagan authors even to begin to exhaust, but cf. Horace “Odes” 1.10: “Mercuri,…/ qui feros cultus hominum recentum/voce formasti…”; Varro, “De Agricultura 134: “Iane pater,…preces precor ut sies volens propitius mihi liberisque meis…”; Virgil, “Aeneid” 3.85: “Da propriam, Thymbraee, domum; da moenia fessis.”

—– Yes, the above is true, and resulted in one of the greatest conversion processes, a process which was used to transmit the Truth in a way the people of the times were able to understand and grasp. In our present day however, this is not the case but an actual effort to undermine Catholicism. With the way the Novus Ordo is being presented today, Truth is not the end result of what the Forma Ordinaria is being used for. It is being used to devolve Catholicism, where the Truths of God and teachings of the Church have been minimized and even spoken of on a contrarian basis.

The Extradordinary Form of the Mass has been around for over 400 years. The growth and development of Western Civilization has revolved around this Mass. The numerous saints who have been elevated to the Altar ( and countless known only to God Himself ) drew their strength and spiriturality from this Mass, and from the way Catholicism was taught and presented. There is nothing about the Tridentine Mass which can in any way be accused of being outdated, or no longer relevant. The Tridentine Mass will, in fact, be the basis on which better spirituality and deeper love of God and the Church will grow and flourish.

Kevin Symonds wrote:

“I do not know if this will help, but I frequent catholicculture.org and they had an article/essay on their site that talked about priestly narcissism and the Mass. It was about priests thinking too highly of themselves to change the Mass around.”

—– In many ways, I find this to be true. I believe this is result of the fact the Novus Ordo has been misunderstood and misused. Facing Ad Populum already re-orients the focus of the Mass. Add to that, the silly ideas they may have about the Liturgy and any theological anomalies they may already have.

Yes, there are a great number of priests today who believe their priesthood all about themselves, not God. A good example of this is the one or two priests whom every now and then reveal their homosexuality to their congregation AT MASS.

Cornelius wrote:

“An excellent source for the relationship of Catholicism to the “culture of modernity” may be found in Tracey Rowland’s work, Culture and the Thomist Tradition: After Vatican II.”

Pertinent to the issue of liturgy is the “culture of deliberate forgetting,” i.e., that the culture of modernity, which is virulently anti-Christian, enforces forgetfulness as a solvent of Christian values and character formation. A culture of deliberate forgetting is also deeply anti-virtue, because virtue is possible only in so far as we understand ourselves as beings in time, with a past that defines our characters.

Liturgy, particularly the TLM, rooted as it is in tradition, is a sort of anti-solvent to cultural forgetfulness and, along with the Church calendar of feasts and solemnities, serves to sanctify time. The TLM, then, may serve as a cultural beacon of what modern culture has lost and can no longer provide on its own.

—– A further support of my premise. Thanks, Cornelius.

Of course, Pope Paul VI couldn’t destroy the Cathedrals throughout the world, but he, through Archbishop Bugnini, unwittingly attempted to destroy the very thing those great Cathedrals were meant to house: the Traditional Latin Mass. Think: those edifices weren’t meant as mere museums to God. They were meant to house a living liturgy, and the liturgy envisaged is the Traditional Latin Mass. How many great Cathedrals have been inspired by the bland Mass of Paul VI?

The great Cathedrals and the extraordinary mass are interchangeable. In a sense, the new catholics usurped our Cathedrals after Vatican II, much as the Arians took over the Cathedrals during the Arian crisis. St. Athanasius said during the Arian crisis: “They may have our places of worship, but we have the faith.”

So, too, today, groups such as SSPX, FSSP, and now small groups of faithful fighting for the Extraordinary form of the mass, may not have the Churches–the physical edifices–but we have the faith. We have the Holy Spirit, guiding us, as did the Early Christians, while the rot continues in the great Cathedrals once occupied by the faithful, but now occupied by heretics….

http://www.traditio.com/tradlib/agatha.txt

Matt Q said:

“The Extradordinary Form of the Mass has been around for over 400 years.”, …. and some centuries, even a millenium, to boot. We do well to recall that Trent did not create the Roman Missal, Pius V simply codified it.

I’m not sure what his question was. I see posts on:

-the impact of liturgy on the culture

-the impact of culture on liturgy

-the ancient pagan influence on Latin prayers in the early liturgy

-the contemporary orientation of celebrants nowdays

So, I’m still not 100% sure.

However, are Paul and Cornelius starting to get at what the original letter is asking?…. Which would be something like: We’ve all seen the inroads of contemporary culture on the celebration of the mass. So, how much has “contemporary culture” affected the mass throughout its history from the beginning, and how can we distinguish what is legitimate and what is not? From the point of view of an expert analysis==> ie serious academic-style work. It sounds like the respondent is asking for something to read on the topic.

Is this correct? And is this the question you are asking by passing this along to us, Fr. Z?

As an additional aside, I think that if there are books/articles pertinent to the question, I think only an excruciatingly honest author, like Benedict XVI, would be worth reading because there is so much partisanship among so many which clouds issues very much.

The other thing that can be noted is that there is some information in Summorum Pontificam itself on the origins and continuity of the Latin Rite mass. A fair statement about the necessity for continuity can be made about the central theology of the Latin Rite mass, either form.

More detail about things outside that centrality could be obtained from reading books written by Josef Ratzinger, that is, Pope Benedict XVI before he became pope. Others may wish to add other intellectually honest and trustworthy references for this kind of information.

@michigancatholic: I was the writer of the original question to Fr. Zuhlsdorf. My question might be restated as: if the pagan Romans contributed worship forms to the latin liturgy, what might our current cultural (or any culture) contribute? This is the project the Consilium set out for itself after the Council. Is such “inculturation” needed? And, to get back to the source, how did the Fathers see this interplay between common culture and the liturgy (if they considered it at all)? Or is this a modern preoccupation?

More here: http://adfontem.com/2007/12/14/a-question-posted-over-at-wdtprs/

Not all cultural forms are fertile ground. Before our age, cultural transmission and integration forms worked through a powerful auditory sensus, and could count on a taken for granted world of symbols–symbols that were understood to point beyond themselves. Ours has been a time of disenchantment and a time of provocative visualization, with a powerful focus on information. This would seem to favor a certain kind of Novus Ordo celebration, at least on the surface. But in the abyss God is also present. I think we’ll see the TLM sharpened, maybe a little less baroque than at one time, more tuned into the structure of the Mass itself and less given to things like sentimental hymnody. We may see its symbolic edges brighter still, in a way that will allow the divine liturgical scalpel to do its repair work. I was looking at the photos of the diaconal ordination in Clear Creek and it was indeed, as commented, a form of noble simplicity. It will take a liturgical scalpel or even heavier equipment to break through the infertile surface ground. But underneath still lie the deep layers out of which the traditional Mass grew over the centuries.

Father M:

Could you explain what you mean when you say the TLM may develop to be a little less Baroque than at one time?

The present situation in the Latin Church is especially interesting because we are in the process of rediscovering tradition after having forgotten it, in a sense. In past ages, when the beliefs and practices of our Faith were clearly part of a lived reality, i.e. with no sense of rupture, they were integrated into the fabric of people’s lives in a way which, while not perfect, was taken for granted. The various components of the practice of the faith stood in fairly clear relation to one another.

Presently, after the rupture of the 60s and 70s, when we are slowly rediscovering the pieces of the puzzle, there is a whole new generation which is having to relearn where everything fits and how things should be structured. The advantage of this is that weaknesses in the way things were done in the past stand out more clearly and there is opportunity to avoid past mistakes. So for example, if Sung Mass is too infrequent in places before, there is opportunity to cultivate its celebration more frequently now. If sappy hymns prevailed in much of the English-speaking world, then there is the chance to avoid such in the future. If Sunday Vespers was too infrequent in places, then this practice can be taken up with fresh vigour. Thus, although many good traditional beliefs and practices are no longer taken for granted, there is the advantage that the traditional weaknesses aren’t either.

Among many “traditionalists”, there seems to have been a desire to resort to forms familiar to them from the 1950s – even the bad things (e.g. too infrequent Sung Mass in certain regions, sappy hymns, etc.). However, as the general rediscovery of tradition matures, this tendency will disappear. More emphasis will be placed on good music, i.e. Gregorian chant and polyphony, and Sung Mass will be celebrated more often as well. We see already that the EF Mass tends to be celebrated much better than it was in many places in the ’50s.

As priests and people become more familiar with the traditional services (I don’t mean just Mass), they will become easier to celebrate and participate in than in this transitional time of relearning.

Please don’t construe my comment on pagan Roman influences in Christian prayer as a justification for what goes on today in the name of inculturation. What culture today is not influenced by the West? And after the Enlightenment altered our basic paradigm of thought about the supernatural there is not much of value our culture is going to contribute to noble liturgical development. About the only accomodation I think necessary is the question of the length of the rites. Modern life had made the pre-Pius XII Palm Sunday liturgy, for example, impossible for the average parishioner. (I think people who love these older forms should be allowed to celebrate them, by the way.) I have no trouble at all (as post-Constantinian theologians didn’t either) in seeing the Romans as a people specially chosen by Divine Providence. Post- modern northern European liturgists cannot claim that role.

M Kr–about Masses that are less baroque:

I think your own post probably states the point very well. The baroque was simply an example, and the baroque itself was an expression of a self-confident, exuberant but AT TIMES overly precious culture and elements of that appeared in the Mass, and some of them inhered in the Mass right up to our time. This is not to say that some of the beautiful Mass settings from the baroque era are not to be used. But I do think many priests and others trying to find their way in this particular renaissance are trying to attend more to the rite itself and to its holiness, rather than any one form of packaging. And that packaging including the sappy hymns and even some of the sweet ones we remember from the 1950s. I believe we can be very intentional about this and try to recover the rite itself–with chant and polyphony. In other words, I have nothing against the baroque–but might have some personal hesitation about modern recreations of 1955 versions of the neo-baroque. That being said, if someone is doing the Traditional Mass and following the rubrics, then baroque or not, let it flower wherever it will.

First one has to ask the question: Does it matter that God chose the time and place that he did? Why that time and not another? Does that context, including Latin, have “pride of place” in some way? Or not? Can and does God work in this way? Or not? How does this work? What does the Church say?

The answers to these questions are surely going to determine the context of contemporary influences for the intellectually honest inquirer. What role does the contemporary milieu have in the continuity of the faith? How much can it, should it, insert into the stream of continuity? More or less than a similar number of years in say, the fifteenth century–or the seventh–or any other? Precisely why or why not?

Malta wrote:

“Of course, Pope Paul VI couldn’t destroy the Cathedrals throughout the world, but he, through Archbishop Bugnini, unwittingly attempted to destroy the very thing those great Cathedrals were meant to house: the Traditional Latin Mass. Think: those edifices weren’t meant as mere museums to God. They were meant to house a living liturgy, and the liturgy envisaged is the Traditional Latin Mass. How many great Cathedrals have been inspired by the bland Mass of Paul VI?

The great Cathedrals and the extraordinary mass are interchangeable. In a sense, the new catholics usurped our Cathedrals after Vatican II, much as the Arians took over the Cathedrals during the Arian crisis. St. Athanasius said during the Arian crisis: “They may have our places of worship, but we have the faith.”

So, too, today, groups such as SSPX, FSSP, and now small groups of faithful fighting for the Extraordinary form of the mass, may not have the Churches—the physical edifices——but we have the faith. We have the Holy Spirit, guiding us, as did the Early Christians, while the rot continues in the great Cathedrals once occupied by the faithful, but now occupied by heretics…”

Malta, such a deep and poigniant observation. It further emphasizes the loss!

You asked this question, “How many great Cathedrals have been inspired by the bland Mass of Paul VI?”

Two examples.

1. The cathedral of San Francisco, California. Looks exactly like what its critics, lay and clerical, Catholic and non-Catholic, say, a washing machine. It’s round and has a spire with a base which cannot look like anything but the agitator of a washing machine. It’s called descriptively, the Washerette.

2. The Cathedral of Los Angeles. An uninpsired sandstone-colored monstrosity which its critics, again lay and clerical, Catholic and non-Catholic, say, an out-of-balance aircraft hangar. Things are off-centered, there are no connected right angles… one gets the feeling of being on board a ship in rough seas. In the courtyard there is a life-size Crucifix LAYING on the ground but slightly upturned on its left cross-beam as though it just happened to have been dropped there. It’s right there in the middle of the pathway and people just have walk around it like it was in the way.

Yes, Malta, again, you are so correct. God bless you in your observations.

Peter wrote:

“‘The Extradordinary Form of the Mass has been around for over 400 years.’, …and some centuries, even a millenium, to boot. We do well to recall that Trent did not create the Roman Missal, Pius V simply codified it.

Thanks, Peter, but your statement is irrelevant to my point. We were speaking specifically of the Tridentine Mass and its point in history to the present day, not whatever form Mass may have been in the past.

Michigan,

Interesting questions all.

Although you speak in hypotheticals, they are interesting.

I think it is interesting how God lets us “flounder” for a while, and then draws us back. He led his chosen people on a goose chase for forty years. God let His Son suffer in the desert for forty days, while He was tempted by Satan. Why did God let his own Son be tempted by Satan? That is a great mystery.

Latin has pride of place for two reasons. One, it was one of three languages posted above the Cross: In addition to Latin, Aramaic and Hebrew were posted above the cross.

Also, Latin was used in liturgy long after it was the vernacular language. For instance, when Charlemagne regularized the liturgy in the ninth century, he regularized the liturgy into the traditional Latin Mass (almost indistinguishable from today’s).

But the Rubrics of the latin mass date to the time of Pope St. Gregory the great in the sixth century. The New Mass is a true novelty….