It stands to reason, in a way.

It stands to reason, in a way.

This is for your Just Too Cool file.

Form phys.org:

Earliest known piece of polyphonic music discovered

New research has uncovered the earliest known practical piece of polyphonic music, an example of the principles that laid the foundations of European musical tradition.

The earliest known practical example of polyphonic music – a piece of choral music written for more than one part – has been found in a British Library manuscript in London.

The inscription is believed to date back to the start of the 10th century and is the setting of a short chant dedicated to Boniface, patron Saint of Germany. It is the earliest practical example of a piece of polyphonic music – the term given to music that combines more than one independent melody – ever discovered.

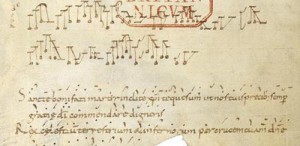

Written using an early form of notation that predates the invention of the stave, it was inked into the space at the end of a manuscript of the Life of Bishop Maternianus of Reims.

The piece was discovered by Giovanni Varelli, a PhD student from St John’s College, University of Cambridge, while he was working on an internship at the British Library. He discovered the manuscript by chance, and was struck by the unusual form of the notation. Varelli specialises in early musical notation, and realised that it consisted of two vocal parts, each complementing the other.

Polyphony defined most European music up until the 20th century, but it is not clear exactly when it emerged. Treatises which lay out the theoretical basis for music with two independent vocal parts survive from the early Middle Ages, but until now the earliest known examples of a practical piece written specifically for more than one voice came from a collection known as The Winchester Troper, which dates back to the year 1000.

Varelli’s research suggests that the author of the newly-found piece – a short “antiphon” with a second voice providing a vocal accompaniment – was written around the year 900.

As well as its age, the piece is also significant because it deviates from the convention laid out in treatises at the time. This suggests that even at this embryonic stage, composers were experimenting with form and breaking the rules of polyphony almost at the same time as they were being written.

“What’s interesting here is that we are looking at the birth of polyphonic music and we are not seeing what we expected,” Varelli said.[…]

Read the rest there.

Included is some modern notation.

Here is a video of the piece being sung.

Not exactly the “My Little Pony” stuff we hear in most churches now.

I don’t know about you, but when I hear early polyphony, such as that of Léonin and Pérotin and other ars antiqua writers I find it eerily moving. These people were steeped, positively drowning, in transcendence. That’s what gives their music a kind of hair-raising quality.

More…

I tend to have this arrogant/ignorant attitude that people centuries ago were rather primitive. I am constantly amazed to discover how wrong I am, and to realize that, all things considered, we haven’t progressed all that much and we aren’t that clever. I was recently reading about the remains of King Herod’s palace that have been unearthed, and was stunned by the ambitious architecture. History is amazing.

Oh what a blessed relief from the PA enhanced shrieking soprano at this morning’s mass. The third selection seemed very like the “Puer Natus Est” of the Christmas Introit, but fancier. Either way it is lovely.

Would that type of music necessitate being preformed by a rehearsed choir, versus the people in the pews singing along as is the current practice?

I would like to propose a “Nothing but Medieval Polyphonic Chant Sunday” for the entire Church. I need Pope Francis’ phone number.

This is very cool. I wonder why it took so long for this to be reported, as I heard this discovery was made in 2012.

Legisperitus – It takes time for a responsible academic to confirm a discovery.

1. Find cool thing.

2. Realize what it means.

3. Research and test to make sure that cool thing is what you think it is.

4. Informally ask buddies, peers, and enemies whether they agree it is cool thing you think it is.

5. Publish article about cool thing.

6. Peer review article about cool thing.

7. Send out press release about cool thing.

Thank you, Reverend Father, for this! What a wonderful Christmas present!

I have long held the view that in the last 50 years the two positive developments (1) in the humanities and (2) in the arts have been in the former the development of the concept of “Late Antiquity” — that there was high cultural life in the European Civilization (aka “Western Civilization”) between a.D. 200 and 800 — and in the later the Early Music revival, starting the the late David Monroe in the late 1960s. Many alive today can remember when Pop Music discovered chant in the mid 90s, right when it was being ignored in the Church.

And I join Fr. Z in celebrating Léonin and Pérotin, the music which was the musical equivalent of Gothic architecture, just as chant was the music of Romanesque architecture. Allow me to provide two examples: first hear the chant “Viderunt Omnes” for Christmas Day, and then hear what Pérotin does with in in the first example of four part counterpoint in European music:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EN73kO2_PZA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bpgaEFmdFcM

A footnote: Pérotin was the inspiration of Steve Reich’s “minimalism” of the 1970s. Hear his “Octet” and you will immediately hear the debt to Pérotin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Np9yApXD94

Yes, this is fairly old news just now picked up by the general media. It’s a bit misleading since no serious scholar every thought polyphony started in the 10 century. There are already instructions in the 9th century on how to do it. This is probably the earliest music outside of a treatise, but if there were treatises, then there was music already in existence by the mid 9th century. The claim that polyphony has somehow already been straight-jacketed by rules is nonsense. The enchiriadis treatises only give one window into the practice.

So moving, it made me cry.

“To sing is to praise God twice”

And to join the discovery of Latin Antiquity with the Early Music Revival, there is the outstanding work of Marcel Pérès and his Ensemble Organum in recording Old Roman Chant and Beneventian Chant. The scholars might fuss that many of Pérès’ elements — the microtones and the drone — are conjectural, yet this version of music for Good Friday is simply sublime: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2JOShBSsql0

Thus the music of Rome herself in Late Antiquity and the Patristic age, something that ought to interest Roman Catholics. For Gregorian Chant didn’t start in Rome and is instead a creation of the Carolingian and Cluny periods, and thus later than Old Roman. To go to the churches of Late Antiquity in Rome –perhaps the best preserved for structure is Santa Maria in Cosmedin and for mosaics Santa Prassede — is to see the world heard in Old Roman Chant.

And it is wonderful to hear music from a time when the the Church was singing “with both lungs”, the Eastern lung and the Western.

Yes, this is an important find, not only because it gives notation for polyphony, but, also because it helps to see if that notation were standardized. The earliest monophonic notation dates back to about 800 A. D. And this sample is only about 100 years later. It seems to be in a variant of heightened neumatic notation. The original notation is above the Latin words and the polyphonic addition is directly above it.

“Would that type of music necessitate being preformed by a rehearsed choir, versus the people in the pews singing along as is the current practice?”

This sort of music was never sung by pew-sitters for two reasons: 1) most were illiterate, 2) none could read music notation. This sort of manuscript would have been found in a monastery or large Church and would have been zealously guarded. The head musician would have trained the other monks in the sound of the music, but not in reading the notation. The memories of these monks were prodigious.

“I have long held the view that in the last 50 years the two positive developments (1) in the humanities and (2) in the arts have been in the former the development of the concept of “Late Antiquity” — that there was high cultural life in the European Civilization (aka “Western Civilization”) between a.D. 200 and 800…”

This discover goes back at least 100 years in the sciences. The famous Catholic physicist, Pierre Duhem, wrote a (yet, untranslated) ten volume treatise, Le système du monde: histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic (The System of World: A History of Cosmological Doctrines from Plato to Copernicus). In it, he showed how the Church was responsible for the development of science during the early Middle Ages. The whole Wikipedia article on Duhem is well worth reading, as it shows how a devout Catholic can approach science. Thus, the apparatus, especially acoustical science, was well in-place by 900 A. D.

“For Gregorian Chant didn’t start in Rome and is instead a creation of the Carolingian and Cluny periods, and thus later than Old Roman.”

This is conjecture. There has been some recent speculation that Western Chant comes from Eastern Chant and this may be correct (it is known that after the Christian diaspora from the early 60’s A. D., many Christians settled in the East) , but the scalar systems of the East and the West are totally different and the microtonal pattern of the East (which isn’t really a scalar pattern, per se) would not have been acceptable in the West. In all likelihood, the words of Chant got passed on to the West and the idea of Chant was solidified (it was already known in the Jewish Synaxis practice), but the music, itself, would have been swapped out for Western tonality.

It is expensive to be a musicologist. It takes longer to become a musicologist than to become a brain surgeon. Think about that. It is the longest academic degree program in universities. I could never had made this discovery, although I was going to write a paper on generalized scalar theory and have submitted entries in competitions for new music notation, because I could never afford to roam through the British museum, sigh. It is a great discovery and hopefully, more examples can be found.

On a related note, one of the reasons I hate the prolonged copyright periods in the West (especially the U. S.) is because historical artifacts, such as manuscripts, can be lost so easily and the more copies of a work in circulation, the less likely it is to be lost.

The Chicken

This is so good maybe you could post it every year. As it is I have come back to it several times.

Fantastic and thanks….