I suppose it is a confluence of factors, including the rhythm of the liturgical year and various factors in life, I found the Introit for today’s Mass, for Pentecost Tuesday, quite moving.

Introitus

4 Esdr 2:36 2:37

Accípite iucunditátem glóriæ vestræ, allelúia: grátias agéntes Deo, allelúia: qui vos ad coeléstia regna vocávit, allelúia, allelúia, allelúia

Ps 77:1.

Atténdite, pópule meus, legem meam: inclináte aurem vestram in verba oris mei.

V. Glória Patri, et Fílio, et Spirítui Sancto.

R. Sicut erat in princípio, et nunc, et semper, et in saecula saeculórum. Amen

Accípite iucunditátem glóriæ vestræ, allelúia: grátias agéntes Deo, allelúia: qui vos ad coeléstia regna vocávit, allelúia, allelúia, allelúia

When I am struck by a verse during Mass, when a particular antiphon stops me in my tracks, I – in my best Indiana Jones imitation – will often hunt up the treasure after Mass to get the context. Sometimes an antiphon is merely a pointer to a larger context, or something else in the chapter which the singer/listener should know.

Now… a question arises. Where to find 4 Esdr 2:36 2:37 in the Bible?

“Esdras”, quoth I. “Why did it have to be Esdras?”

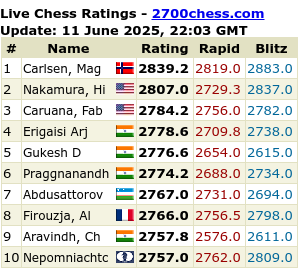

Esdras is complicated. Here is a handy chart from wikipedia which shows the various ways the books of Esdras are named and numbered.

Clement VIII, who revised the Vulgate after the Council of Trent to reflect the Council’s canonical list of recognized books of the Bible, moved the “Prayer of Manasses”, 3 Esdras and 4 Esdras into an appendix, “ne prosus interirent… lest they entirely perish”. Protestant Bibles number these books differently and what is 4 Esdras in the Vulgate is 2 Esdras in the KJV.

Here is another chart, from here.

Catholics are interested in 4 Esdras for a variety of reasons. For example, the prayer “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine” is based on 4 Esdras 2:34-35.

Hey. Wait! That’s our chapter for the verse for the Introit today, no?

Yes!

Here is something from the Catholic Encyclopedia about 4 Esdras:

Fourth Book of Esdras

The personage serving as the screen of the real author of this book is Esdras (Ezra), the priest-scribe and leader among the Israelites who returned from Babylonia, to Jerusalem. The fact that two canonical books are associated with his name, together with a genuine literary power, a profoundly religious spirit pervading Fourth Esdras, and some Messianic points of contact with the Gospels combined to win for it an acceptance among Christians unequalled by any other apocryphon. Both Greek and Latin Fathers cite it as prophetical, while some, as Ambrose, were ardent admirers of it. Jerome alone is positively unfavourable. [No surprise there.] Notwithstanding this widespread reverence for it in early times, it is a remarkable fact that the book never got a foothold in the canon or liturgy of the Church. Nevertheless, all through the Middle Ages it maintained an intermediate position between canonical and merely human compositions, and even after the Council of Trent, together with Third Esdras, was placed in the appendix to the official edition of the Vulgate. Besides the original Greek text, which has not survived, the book has appeared in Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopic, and Arabic versions. The first and last two chapters of the Latin translation do not exist in the Oriental ones and have been added by a Christian hand. And yet there need be no hesitation in relegating the Fourth Book of Esdras to the ranks of the apocrypha. Not to insist on the allusion to the Book of Daniel in xii, 11, the date given in the first version (iii, 1) is erroneous, and the whole tenor and character of the work places it in the age of apocalyptic literature. The dominant critical dating assigns it to a Jew writing in the reign of Domitian, A.D. 81-96. Certainly it was composed some time before A.D. 218, since it is expressly quoted by Clement of Alexandria. The original text, iii-xiv, is of one piece and the work of a single author. The motive of the book is the problem lying heavily upon Jewish patriots after the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. The outlook was most dark and the national life seemed utterly extinguished. In consequence, a sad and anxious spirit pervades the work, and the writer, using the guise of Esdras lamenting over the ruin of the first city and temple, insistently seeks to penetrate the reasons of God’s apparent abandonment of His people and the non-fulfilment of His promises. The author would learn the future of his nation. His interest is centered in the latter; the universalism of the book is attenuated. The apocalypse is composed of seven visions. The Messianism of Fourth Esdras suffers from the discouragement of the era and is influenced by the changed conditions produced by the advent of Christianity. Its Messias is mortal, and his reign merely one of happiness upon earth. Likewise the eschatology labours with two conflicting elements: the redemption of all Israel and the small number of the elect. All mankind sinned with Adam. The Fourth Book of Esdras is sometimes called by non-Catholics Second Esdras, as they apply the Hebrew form, Ezra, to the canonical books.

Also, Esdras is found as a Saint in the 2005 Roman Martyrology for 14 July:

2. Commemoratio sancti Esdrae, sacerdotis et scribae, qui, tempore Arataxeris regis Persarum, Babylone in Iudaeam rediens populum dispersum congregavit et omni studio enisus est, ut legem Domini investigaret, impleret et doceret in Israel.

I will let one of you tackle that pithy entry. A nice example of the use of the imperfect subjective after a perfect verb… all that sequence of tenses stuff.

In any event, you can access the text of 4 Esdras here.

Here is 4 Esdras 2:33-40 in the RSV:

I, Ezra, received a command from the Lord on Mount Horeb to go to Israel. When I came to them they rejected me and refused the Lord’s commandment.

Therefore I say to you, O nations that hear and understand, “Await your shepherd; he will give you everlasting rest, because he who will come at the end of the age is close at hand. Be ready for the rewards of the kingdom, because the eternal light will shine upon you for evermore. Flee from the shadow of this age, receive the joy of your glory; I publicly call on my Savior to witness. Receive what the Lord has entrusted to you and be joyful, giving thanks to him who has called you to heavenly kingdoms. Rise and stand, and see at the feast of the Lord the number of those who have been sealed. Those who have departed from the shadow of this age have received glorious garments from the Lord. Take again your full number, O Zion, and conclude the list of your people who are clothed in white, who have fulfilled the law of the Lord. The number of your children, whom you desired, is full; beseech the Lord’s power that your people, who have been called from the beginning, may be made holy.”

Turning to my beautiful Baronius Press edition of the Scriptures, having in parallel columns the Douay-Rheims Version and the Clementine Vulgate, I found the passages used for the Introit for the Mass of Pentecost Tuesday.

Useful book. And beautifully bound.

So, there is something of the text for the Introit in the Extraordinary Form.

The commemoration of holy Ezra, priest and scribe, who, in the time of Artaxerxes king of the Persians, returning from Babylon to Judea the dispersed people, having gathered them, and having exerted himself in all study, that the law of the Lord having been investigated, it might be implemented and made known in Israel.

What are you, Father–clairvoyant?!! Sunday after Liturgy, someone recommended that I buy this very edition (Baronius) and then yesterday they called to say they had an edition for me!

And probably because of the reading of this blog, I, too, have been paying better attention to lines that strike me during the Mass/Liturgy and doing similar little (baby step) investigations into the Catena Aurae, etc. (thanks to the iPieta app on the iPhone). It’s such a rich, rich deep world — and we are satisfied with so very little.

The affirmation all round is stunning.

Father Z – Very nice; I have been tapping into Pope Paul VI’s grief over the loss of the Pentecost octave (your point yesterday about the stopping of liturgical time was a very helpful insight for me), so I appreciate this in-depth exploration of these prayers, since I’m not QUITE ready to move on to Ordinary Time yet (as my dear friend ScienceGirl said, how can people complain that the Church pre V2 used to give short shrift to the Holy Spirit when there was a whole OCTAVE for Pentecost that got removed post V2???!).

Carl b – Not bad at all! May I humbly (if pedantically!) suggest just a couple of corrections?

1) Unlike “return” in English, rediens (<redeo, for those of you keeping score at home) is intransitive. Accordingly, the sentence here emphasizes Esdras' return from Babylon, not that of the people. He does not "return" the people to Judaea; he just gathers them once he is there.

2) Studium is a lot broader in Latin than in English. Hence something more like "effort" or "zeal" would be better here.

3) It would be more clear to translate the final verbs actively–as they are in Latin–rather than passively.

It is Esdras who is the subject of all of verbs of the purpose clause, and the law that is the object. You have translated it as though it were "ut lex Domini investigata impleretur et doceretur in Israel."

Here is my own rough version of about half of it, highlighting these points:

"who… upon his return to Judaea from Babylon, gathered the scattered populace and strove with all his zeal to delve into, fulfill, and teach (hooray for tricola!) the law of the Lord in Israel."

Ut omnes in Christo pancratice valeatis! ;) Pax.

So far as I can see from quick inspection, the following Bibles in English translation do not include Esdras 3 and 4: Douay-Rheims (Baronius ed.), Douay-Rheims (Tan ed.), RSV CE (Ignatius), RSV CE 2e (Ignatius), New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible.

The only Catholic Bible that I’ve got that does include them is the Baronius Douay-Rheims / Clementine Vulgate Latin-English version that Father Z cites. What a valuable resource this is! The introduction to its appendix including these two books cites the following fascinating paragraph from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

“The Fourth Book of Esdras is reckoned among the most beautiful productions of Jewish literature. Widely known in the early Christian ages and frequently quoted by the Fathers (especially St. Ambrose), it may be said to have framed the popular belief of the Middle Ages concerning the last things. The liturgical use shows its popularity. The second chapter has furnished the verse Requiem æternam to the Office of the Dead (24-25), the response Lux perpetua lucebit sanctis tuis of the Office of the Martyrs during Easter time (35), the introit Accipite jucunditatem for Whit-Tuesday (36-37), the words Modo coronantur of the Office of the Apostles (45); in like manner the verse Crastine die for Christmas eve, is borrowed from 16:53.”

How have “we” survived so long, not knowing about this so liturgically indispensable book? And certainly we need to bring back the medieval belief in the last things which it apparently inspired.

Pedantic,

Thank you so much for correcting me. How could I have missed that the verbs at the ending are active and not passive? My Latin teacher wasn’t lying when she said we ought to practice over the summer, lest we forget everything.

As Henry Edwards notes, 3 Esdreas, 4 Esdras, and the Song of Manasses do not appear in most “Douay-Rheims” bibles that are now available.

There is an edition of the original Douay-Rheims whose New Testament dates from 1582 and Old Testament from 1635 that contains these that is available in facsimile in either five volume book form or in one pdf file on CD (245 MB) from http://www.churchlatin.com/books.aspx?categoryid=18 . The CD appears to be almost a give-away in price ($20), and it is a great thing to have on a laptop. The text shown above of 4 Esdras 2:33 is the same shown in the 1635 text.

My questions: Do *any* Challoner DH translations contain these sections? Did Bishop Challoner even include those in his translation?

You guys have all these insightful things to say, and my only thought was “AGH! I *could* have used Uriel for my 4th kid’s middle name!” I figured we’d run out of Roman-Catholic-approved angel names after Michael, Gabriel and Raphael. But Uriel is the messenger in 4 Esdras, and we could have gone with that.

Great! and here I was thinking the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible was the best thing that wasn’t the Vulgate/Douay-Reims and It’s missing two whole books!!!! Now I’m Mad!!!!!! Why did the Novus Ordo/Concillar Church omit these books!!!!! Someone should alert Pope Benedict and get him to release a new edict saying all Catholic Bible makers should include these books!

At the moment I cannot find the reference, but I believe that Christopher Columbus found a passage in 3rd or 4th Esdras that gave him encouragement to sail west. It was something to do with a round world or a new world.

Young Can. RC

These books are not part of the Bible, therefore no edition is “missing” them.

What other apocryphal books are used liturgically?

If the online version of the venerable Haydock edition of the Douay-Rheims Bible is complete, then it does not contain Jerome’s appendix with the two additional books of Esdras and the Song of Manasses. Does anyone have a copy of a recent reprint to check?

Carl B:

Fortuna fortibus favet, at least when it comes to learning language. You jumped in and took a good shot at it, and got most of it right. This is great! I think a problem we often have in the world of classical language study is that we feel like we have to get everything absolutely perfect all the time. This is NOT a helpful ethos for mastering languages that are already hard enough as it is. Itaque bono animo esto! Bene fecisti! Now why not come along and speak Latin sometime in Kentucky, or in Washington, or in West Virginia, or in Rome, or in Florida with the Family of St. Jerome, etc…

(that’s an open invitation to ALL of you: the number of spoken Latin colloquia is growing, even as the number of your excuses not to come to one is DWINDLING; hope to see some of you at one sometime! Ut valeatis!)

After much searching, I’ve found several sources that answer my question above about whether 3 Esdras, 4 Esdras, and Prayer of Manasses appear in *any* Challoner-Douay-Rheims translation. The sources agree with a summary found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douay%E2%80%93Rheims_Bible which states that these three books are NOT in Challoner’s 1750 translation of the DR Bible. You will search in vain for these in any Challoner translation, which unfortunately is often almost universally and very incorrectly referred to as the “Douay-Rheims”.

Use the *authentic* Douay-Rheims translation, not the Challoner translation.

The other bible that I have containing these three books is…yes…the KJV with Apocrypha!