In the UK’s best Catholic weekly, the Catholic Herald (which sports my regular column in the print edition – SUBSCRIBE!), there is republished a note about comments made by Pope Francis about reading Amoris laetitia. The Pontiff spoke off-the-cuff to some Columbian Jesuits and opined:

“I want to repeat clearly that the morality of ‘Amoris Laetitia’ is Thomist”.

Some defenders of the objectively ambiguous elements of Amoris, which have caused so much confusion and manifest division, immediately started hopping up and down and pointing, “See! See! Indirect response to the Dubia! And 2+2=5!” Fishwrap, for example: “Francis responds to critics: Morality of ‘Amoris Laetitia’ is Thomist”

It is always interesting to read what Popes think, but let’s not get too oyfgetrogn about off-the-cuff remarks, which have no official weight.

Here’s the story:

Seeing, understanding and engaging with people’s real lives does not “bastardise” theology, rather it is what is needed to guide people toward God, Pope Francis told Jesuits in Colombia.

“The theology of Jesus was the most real thing of all; it began with reality and rose up to the Father,” he said during a private audience Sept. 10 in Cartagena, Colombia.

Meeting privately with a group of Jesuits and laypeople associated with Jesuit-run institutions in Colombia, the pope told them, “I am here for you,” not to make a speech, but to hear their questions or comments. [So, from the onset he didn’t intend to resolve anything.]

A Jesuit philosophy teacher asked what the pope hoped to see in philosophical and theological reflection today, not just in Colombia, but also in the Catholic Church in general.

Philosophy, like theology, the pope said, cannot be done in “a laboratory,” but must be done “in life, in dialogue with reality.” [Can’t it be done in both settings?]

The pope then said that he wanted to use the teacher’s question as an opportunity address — in justice and charity — the “many comments” concerning the post-synodal apostolic exhortation on the family, “Amoris Laetitia.”

Many of the commentaries, he said, are “respectable because they were made by children of God,” but they are “wrong.”

“In order to understand ‘Amoris Laetitia,’ you must read it from the beginning to the end,” reading each chapter in order, reading what got said during the synods of bishops on the family in 2014 and 2015, and reflecting on all of it, he said. [Okaaaaay…. ]

To those who maintain that the morality underlying the document is not “a Catholic morality” or a morality that can be certain or sure, “I want to repeat clearly that the morality of ‘Amoris Laetitia’ is Thomist,” that is, built on the moral philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, he said.

One of best and “most mature” theologians today who can explain the document, he told them, is Austrian Cardinal Christoph Schonborn of Vienna. [There are other theologians out there, as well-prepared as Card. Schonborn, who asked for clarifications.]

“I want to say this so that you can help those who believe that morality is purely casuistic,” he said, meaning a morality that changes according to particular cases and circumstances rather than one that determines a general approach that should guide the church’s pastoral activity. [Go back and read that again. Slowly. I have to scratch my head a little, because, as it seems to me, if I am not mistaken, there are those who read Amoris as saying that each case must be considered individually and that different outcomes can result in individual cases, such as in the cases of those who are civilly divorced and remarried being admitted, maybe, to Holy Communion. Wouldn’t that be “casuistic”. On the other hand, those who are seeking greater clarity about the controversial elements of Amoris, if I am not mistaken, hold that there is a general principle which cannot be abandoned in individual cases. So, how is it again that we are to “help those who believe that morality is purely casuistic”? Does the meaning of that phrase depend on the word “purely”?]

The pope had made a similar point during his meeting with Jesuits gathered in Rome for their general congregation in 2016. There he said, “In the field of morality, we must advance without falling into situationalism.”

“St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure affirm that the general principle holds for all but — they say it explicitly — as one moves to the particular, the question becomes diversified and many nuances arise without changing the principle,” he had said. It is a method that was used for the Catechism of the Catholic Church [?] and “Amoris Laetitia,” he added. [I need a sound Thomist to help me out with that. It sounds as if the principle of non-contradiction is in play here, but I could be wrong. If a “general principle” can be turned 180° through nuances, then… is it a general principle?]

“It is evident that, in the field of morality, one must proceed with scientific rigour and with love for the church and discernment. [With “scientific rigor”… as in a, say, “laboratory”?] There are certain points of morality on which only in prayer can one have sufficient light to continue reflecting theologically. And on this, allow me to repeat it, one must do ‘theology on one’s knees.’ You cannot do theology without prayer. This is a key point and it must be done this way,” he had told the Jesuits in Rome.

I’ll have to pray on this for a while.

The moderation queue is ON.

In ch. 8 of AL, footnote 347 refers to the Summa, I-II, q. 94, a. 4. But to me it seems that AL is taking Thomas out of context here. Thomas is talking about the natural law, whether it is the same for all men (yes), and the difference between speculative and practical reason. That’s where he gets into the details, that some practical conclusions from the general precepts of natural law may differ.

But in AL, the topic is not just marriage according to the natural law, but the sacrament of marriage that we received from Jesus Christ. So I don’t think this quote is all that relevant. Besides, by practical conclusions, it seems to me St Thomas means how to act in particular situations so that the general precept of the natural law will be upheld. He uses the example of restoring goods to their rightful owner. There may be some situations, he notes, when it wouldn’t be prudent to do that. But that is not the same as stealing.

Perhaps some other Thomist could clarify this more.

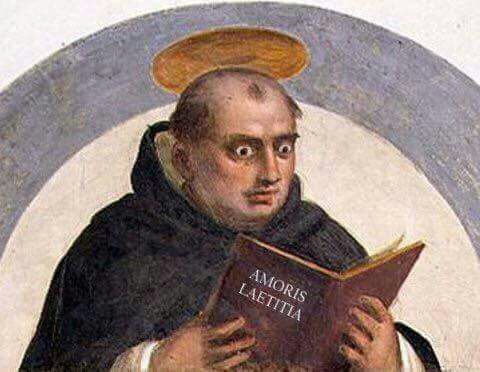

Love the picture at the end! I’ll keep praying too.

…the morality of ‘Amoris Laetitia’ is Thomist,” that is, built on the moral philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, he said.

I am no theologian and I’m not even well read… So I can’t say whether the morality of AM is built on the philosophy of Aquinas. But didn’t Aquinas pose a lot of questions, questions from all sides of a subject and then answer them?

We need answers!

I cannot see in St Thomas’ Catechism any mention at all of a “pastoral solution” whereby the divorced-remarried might gain access to the Sacraments except by penitence and abstinence and their matrimonial & sacramental duty before God and His Church …

http://jimmyakin.com/the-catechism-of-st-thomas-aquinas-18

So how is possibly the exact opposite of Aquinas’ rigorous approach to theological questions such as this one “Thomist” ?

There is another sense where the imposition of a lack of debate within the Roman Curia in particular fails to be Thomist ; Aquinas’ methodology was firmly grounded in the Mediaeval & Renaissance practices of rationally-guided Pro et Contra discussion, including the exam of dissenting views with a view to attempting syntheses, conclusions, and opinions for the purposes of our shared Catholicity — so how exactly is the apparently willful refusal to engage in such debate for the purposes of discovering truths that all should accept a “Thomist” theology ?

(I do find that the word “thomist” is one of the most mis-used words in modern theology since the end of the 19th Century, but after WW1 and WW2 increasingly so, particularly by those having no grounding in Mediaeval or Renaissance Literature studies)

In the field of morality, we must advance without falling into situationalism.

Morality doesn’t advance. What is moral today cannot be immoral tomorrow or vice versa.

as one moves to the particular, the question becomes diversified and many nuances arise without changing the principle.

Morality isn’t a principle, it is an unchainging fact. As one moves to the particular, it is possible to reduce accountability (e.g. society and family taught you than an evil is a good, or one tells a lie to save some’s life) and it is possible that something that is misclassified as a sin (e.g. Lying is a moral sin, but jocose lies are told for the purpose of affording amusement wouldn’t be a mortal sin otherwise all fiction including the Narnia series and all games where deception is involved should be avoided by Catholics).

“It is evident that, in the field of morality, one must proceed with scientific rigour and with love for the church and discernment.

This is false. Science cannot be applied to morality since the principles of science are by nature amoral. In addition, science never proves anything; it only shows that it is reasonable to believe certain things with a high degree of confidence and unreasonable to believe other things with a high degree of confidence. As such, anything derived from science is subject to change. It’s reasonable to believe the world is the center of the universe, until it’s more reasonable to believe the the sun is, until it is more reasonable to believe that there is no center of the universe, until it is more reasonable to believe that every point is the center of the universe. Morality can’t work that way, not matter what the utilitarians and Marxists say.

What science can help is in the discovery of the physical nature of the physical world. From the time of Aristotle to Aquinas it was commonly thought that pre-born humans went through the plant then animal then human phases in their development. Although abortion was always mortal sin, it could be argued that if an infant was killed before he became human the accountability was less. Modern science has shut down this argument since a human is a human from the time of conception. Similarly medical science has made it possible for some “hard cases” in morality to have a more clear cut assessment.

I think our current situation is a great example of Papal infallibility. Proof that God safeguards the teachings of His Church. Francis as Pope in an official cannot officially answer the Duibia or Correctio, at least not maybe in the way he would like. He cannot change the teaching of the Catholic Church.

Unfortunately that doesn’t mean the minds of what the majority of Catholics think the teaching of the Church is cannot be changed. The teaching cannot be officially changed to allow adulterers to receive Holy Communion, but it can be sidestepped, crushed, burned and buried.

If you tell enough people that a dog is a cat, and enough of them start repeating that a dog is a cat, then for all incense and porpoises it is a cat. Or if you tell enough people that a man is a woman, there is plenty of that going around.

This is straight garbage.

I know a Polish teacher who has written (in Polish) a definitive study on the use of St. Thomas Aquinas in “Amoris Laetitia.” He has discovered that the Thomas references are consistently weighted in a direction CONTRARY to that of the main text, and believes that whoever compiled the Thomistic citations may have been attempting, in a subtle way, to oppose the errors of the main text. This research should be available soon in English.

That picture…can not stop laughing.

On the topic, Pope Francis, as typical, seems to be all over the map here. It is hard to systematize and boil down the thought of an individual who is not systematic in their philosophical approach.

I am not a Thomist (as I am not an Aristotelian), but I don’t see how any of this is Thomistic in thought or approach. THE MIND THAT IS CATHOLIC by Fr. Schall s.j. is a fantastic exploration of a (Thomistic) Catholic mind. [US HERE – UK HERE] There isn’t congruence between a Thomistic mind and what one sees in AL or in the above comments of Pope Francis. These are different things.

Let’s narrow in on the Pope’s comment about philosophy in a laboratory rather than in reality. What is he saying here? He is saying that philosophy cannot go from the general to the specific which is 180 from what St. Thomas teaches in the Summa.

The Holy Father speaks here a bit on reality. What is he meaning? Is he not equating reality with the individual’s subjective experience of his present situation? Thus, is not entering into reality rather setting aside one’s own subjective experience of ones personal present situation in order to accompany another person in their subjective experience of their situation?

Seeing how the Holy Father speaks of Jesus, is there not an important question: Is this Pope Francis’ soteriology — Jesus leaves behind the reality of the Godhead in order to enter into man’s subjective reality, to accompany man and be present with man in man’s reality?

Can this all be joined up with the thought that it really is man who saves God that one sees bandied about by the heterodox? In Jesus’ leaving behind the Father’s space and entering into the individual’s situational time, the accompaniment of man allows the Son to be teachable and “to grow in wisdom” of what man’s experience of time is? In the accompanying of man, Jesus bridges the gap between the Father and man by learning the subjective reality of the individual and learning to appreciate each situation for what it is and returns this to the Father allowing the plasticity in the Godhead?

This is the problem. Pope Francis won’t explain himself, so he is open to being used by people and open to people starting to draw conclusions. If you don’t define yourself, you let other people do it for you.

The use of the word “casuistry” here is very problematic.

As a neutral word, it simple refers to studying “cases”, in order to understand how to apply a general principle to a variety of circumstances. Lawyers have to know jurisprudence, case histories, in order to interpret laws in the courtroom. Moral theologians and confessors need to apply moral principles to the lives of individual persons. But the word “casuistry” has sometimes acquired a negative connotation, almost equivalent to “sophistry”, “laxism”, or “situation ethics”, when it seems that there can be an exception to almost every moral norm; as when Jesus condemned the Pharisees for setting aside the law of God for the sake of human traditions.

Ironically, the Jesuits became famous, and infamous, for teaching moral theology with a heavy dose of hairsplitting “case history” to illustrate, or sometimes, perhaps, to obscure, general moral principles. Hence, the pejorative use of the word “jesuitical”, (meaning crafty, sly, intriguing; referring to the use of subtle or oversubtle reasoning; practicing casuistry or equivocation).

The “lamentable” ex-Jesuit modernist, George Tyrrell, once said that if the Jesuits were accused of killing three men and a dog, they would invariably produce the dog alive.

It seems that some Jesuits, of a certain age, have learned to disdain their earlier training as mere “casuistry”, even though they may still retain the deeply ingrained habits of casuistic reasoning. Various interpretations of Amoris Laetitia seem tinged with the very “casuistry” that is attributed to those who seek a clarification of the dubia.

I wish I understood better what people mean when they say someone is a Thomist or Augustinian or something else. I have read the Sims and the Confession so I have an intuitive idea, but not the formal definition. I can also understand intuitively the Popes document, and I can understand the many questions. I understand the difference between reading something and reading into something: I suspect the pope wants people (priests) to put their politicking aside. From following this I see a lot of politics.

I confess that I have not tried to parse the Pope’s comments but they struck me as deliberately vague and non-committal. The “go ask Cardinal Schonborn, he knows” ploy is what I call “getting the run around.” Reading the comments reminded of a certain headline from some time ago: “Ha Risposto! …Si e no.”

I get the impression that Pope Francis considers ambiguity and vagueness to be a virtue. No let your yes mean yes and no mean no for him (unless we’re talking personnel matters). “Twas in another life time, one of toil and blood, when vagueness was a virtue, the road was full of mud.”

“The theology of Jesus was the most real thing of all; it began with reality and rose up to the Father.”

No, no and . . . no. “It” all began with the Truth and the Truth descended from the Father through the Son to us. The Truth is perfect reality – what actually IS. Human “reality” is a hybrid of truth and lies resulting from our fallen human nature. We see through a glass darkly. Apparently, for Pope Francis, the shadows are supposed to define the sun.

It is fascinating, nonetheless, to see the Holy Father replace “Truth” with “reality”.

Admittedly I don’t know what folks mean when they say “Thomism” because it’s used to so vaguely, sometimes as a mere substitute for “Catholic”. However, what Pope Francis has been saying sounds like what Jimmy Akin and Tim Staples were saying many months ago (as well as Bishop Robert Barron in his comboxes on YT):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4c00Dl6VTDw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNA-HLYz1wE

Catholics cannot receive the Eucharist in a state of mortal sin, however the sin can be attenuated in gravity by various conditions. Establishing a certitude of one’s state, given the amount of particular nuances, in these specific cases is to be determined at a more local level (internal forum, help of a priest etc). In the end, after a penitential path and the aforementioned certitude is established, some may receive. The Pope is changing the practice not the doctrine regarding the indissolubility of marriage or the “worthiness” to receive sacraments. In no case whatsoever can someone knowingly receive the Eucharist in a actual state of mortal sin. That’s how I, albeit “most fallibly”, understand the controversial parts of AL and what the Pope has been saying on this matter. I’m not going to speak to wisdom of this whole affair, but I admittedly see some of these distinctions incorporated by the original Kasperite proposal. There is a difference between mortal sin and venial sin, and we know mortal sin requires those famous 3 conditions, right?

Love that picture of St. Thomas and can well imagine that would be the first of his reactions perhaps followed by some choice words. And, golly, I thought the A L was more in line with the kissing bishop ghostwriter than St. Thomas; who knew?

It all depends upon what you mean by “Thomistic.”

Perhaps what the Holy Father means by “Thomistic,” as it applies to AL, is that the Holy Father himself agrees that, in the disciplines of theology and philosophy, the work and thinking of the Angelic Doctor (St. Thomas) have been enshrined for centuries as the source – sine qua non – of the Church’s most foundational principles, and one of the supreme authorities, second only Holy Writ itself.

And his references to the Thomism present in AL are expressions of the Holy Father’s desire to invite and call upon all of the faithful – philosophers, theologians, other scholars, bishops, priests, deacons, religious, missionaries, catechists, and the laity – to regard the principles and the thinking undergirding AL in the same light. As foundational to Church teaching. As worthy to be enshrined, and supremely authoritative. *That’s* how AL is Thomistic.

And if . . . (getting into hypotheticals here, always dangerous shoals) . . . if the Angelic Doctor himself were to arise from his tomb, and were to sit down and read AL from start to finish, the opinion of the document that he would give would almost certainly be: “the fruit of my work is not present in any manner whatsoever within this work (AL).”

And in response, I’m afraid, (getting further into hypotheticals here) Pope Francis would declare Saint Thomas to be an “SAPN” (“self-absorbed Promethean neo-Pelagian”), and that would be that.

I would love for some modern Thomists to weigh in on this claim that AL is “Thomist.”

Pope Francis has used the word “casuistry” in the past in a sense which was completely opposite to what we understand it to be. It was discussed in some blogs at the time. But he is always using terms in unheard of ways. Just provides more confusion.

Thank you for the picture! Got a good laugh — which I so needed. I’ll be printing it out to help me bear all this.

@Dan….You really had me thinking, until you got to incense and porpoises.

@anyone who cares to read a non-anti-Francis comment….Seeing His Holiness preside over Mass in Colombia and listening to his homily, I find it hard to vilify him. For one thing he says things in a way different from the way in which an English speaking North American might be accustomed. His homily was thought-provoking, engaging. For another thing he seems to have aged a fair bit since assuming the papacy. It might not be long before he’ll need one of those walkers with a built-in seat to get around.

What to say about Amoris? I tend to think the pope showed his hand whenever he opined that a great majority of Catholic “marriages” are invalid. Well, what do you do as the Supreme Pontiff when you have umpteen million invalid marriages on your hands? Do you stop everything and focus 98% of the Church’s energy toward processing all these suspect “marriages” through the tribunal process? Or do you kick the problem over to the “internal forum”? Now the purpose of the tribunal is not to *make* a “marriage” null but rather to investigate whether it is null from the get-go, right? So given this context I can understand the impetus behind circumventing the tribunal process and kicking the problem over to the so-called “internal forum”. This option becomes especially attractive if one considers the “internal forum” to be just as competent as a tribunal at discovering the facts of any given case.

Didn’t Aquinas say that an appeal to authority is the weakest of all arguments? I wonder what he would about the Holy Father’s appeal to the authoritative weight of Thomism as an argument in favor of AL’s truth.

Fr Basil Cole OP has written on the ‘Thomism’ of AL at the NCR (http://www.ncregister.com/blog/edward-pentin/is-amoris-laetitia-thomistic) and the HPR (http://www.hprweb.com/2017/09/further-dubia-for-the-confused/) which may clarify things. He seems to be saying that Thomas is being taken out of context.

I think Fallibilissimo may be right but what does not seem to be acknowledged by AL and its defenders is that the culture within the Church has changed (at least in the West). The ‘internal forum’ approach presupposes Catholics in ‘irregular relationships’ going to confession. My experience here in Ireland is that they are not and I am presuming that is probably the case across the West. They don’t even go to Mass on Sunday. They might show up at Christmas and probably a funeral (BIG thing here even you are not a relative). Even regular, ordinary Catholics are not frequent attenders at Confession. We all know there is a lot of ignorance, confusion and disinformation out there among our fellow believers. I haven’t come across people in the situations envisaged in AL seeking to receive Holy Communion. They’re not banging on the doors to come in. They simply get in the line at a Mass or choose not to receive. It makes me wonder what is really behind this.

This off-the-cuffing style is degrating to the office of the Papacy, as much as Donald Trump’s tweets are to the office of the Presidency. It is undignified and prone to misinterpretation.

Father, I read an excellent article yesterday (link below) by a Dominican that analyzes the claim that AL is “Thomist” and the answer is clearly no. Perhaps you have already seen it.

I was shocked after reading Pope Francis’s claims to the effect that is it(!). It is such a bald-faced falsehood, so 180 degrees opposite the truth that I was stunned the Pope could actually assert something like that with such brazen audacity (could he actually believe that…..?).

In our benign (naive?) desire to put the best face on things, such sweeping assertions throw us off. We think that when a man makes such statements categorically that there must be truth in it. And for many Catholics, these statements are taken at face value, putting the “thinking” Catholic who raises objections in a bad light.

The manner in which the Holy Father and his allies say completely the opposite not only of the truth, but of the constant teaching of the Church and the absolutes given to us in Divine Revelation, is becoming frighteningly diabolical. Will they stop at nothing?

This crisis clearly has satan’s fingerprints and hallmark all over it.

Here is the article:

http://m.ncregister.com/blog/edward-pentin/is-amoris-laetitia-thomistic#.Wc6bH8aQypq

General principles of the moral law can be inadequate to address particular cases. It is not that the natural law itself no longer applies. It is against reason (and therefore against the natural law) to restore an entrusted weapon to its owner under certain circumstances (as Thomas explains).

It has not been shown so far, at least to my satisfaction, how extramarital relations would admit of such an exception. On the one hand, there are the rights of the presumed spouse (in the case of adultery), rights which derive both from Divine and ecclesiastical law which are trashed by the presumption to live more uxorio with another and especially if presented publicly as marriage. On the other hand, there are the rights of the possible child conceived, born into an irregular union – the chief problem with adultery, as Thomas explains. Not only is it a bad example, but it also risks material welfare – if there has been one divorce or abandonment, what prevents another, especially given the lack of a real binding union?

And…in sum:

“Woe to you that call evil good, and good evil: that put darkness for light, and light for darkness: that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter.”

With all respect to the Holy Father, I keep thinking of a quote from Newman’s Loss and Gain: “My good friend here certainly has not the clearest of heads.”

@PTK70

The internal forum sounds great until you think about what it does to due process. If Fr. Pastor waves his hand over Mr. So-and-So in his office – or even worse, in the confessional – what does he say when the first Mrs. So-and-So shows up in the parish asking why her husband is with this other woman and is receiving Holy Communion when it is public knowledge that he is still bound to her?

It happens. And it is a mild earthly foretaste of the judgment and wrath which these poor misguided priests will endure on the Last Day.

Spouses have rights. Even if they don’t want to use them, they must be respected. These “rigid laws” exist to keep order, and ultimately to protect souls.

Anyone who has a strong temptation to sympathize with the Kasper/internal forum proposal should imagine what it would be like if something similar was done in merely civil law. It would be a plaintiff who does not go to court but privately discerns – possibly with the help of a police officer or lawyer – that he can go ahead and punish the one he thinks guilty in accord with what the law provides for. Suppose it is a matter of armed robbery, which calls for 25 years imprisonment. If the “plaintiff” reached a sure judgment that this individual really did the crime, could he therefore lock him up in the basement for 25 years? No. That is called kidnapping, even if there really was such a crime. Such due process (specifically “innocent until proven guilty in public court” or in this case “valid until proven invalid in public court”) is a real obligation so long as there is a court to provide judgment.

There are some gray areas with these matters, such as so-called “conflict marriages” (where a petitioner is unable to provide objective evidence due to an impediment – rather than simply not having any – which is extraordinarily rare, and a tribunal is not really built to handle), but this is just not what AL is about, is it. It would be easy to state the special kinds of cases were there any specific ones in mind. Instead we get consequentialist justifications of adultery in canonically unambiguous situations, such as potentially harming the children or occasioning suicide.

The Pope’s comment is a direct reference to this passage in Chapter 8 of AL:

I earnestly ask that we always recall a teaching of Saint Thomas Aquinas and learn to incorporate it in our pastoral discernment: “Although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects… In matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles; and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all… The principle will be found to fail, according as we descend further into detail”. It is true that general rules set forth a good which can never be disregarded or neglected, but in their formulation they cannot provide absolutely for all particular situations.

So he quotes St. Thomas. But he does so out of context, and indeed as a bit of proof-texting, as I put in in my own comments on AL, here: http://whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2017/01/when_the_rome_hits_your_eye_th.html

As is usually the case with difficult passages from St. Thomas, there is a right way and a wrong way to go about understanding him. Generally, there are clues that should point us away from the wrong ways, even if it is not entirely clear. Here, the important clues are that twice he states that the kinds of departures he is talking about are FEW: “failing in a few” and “yet in some few cases”. And his example: when it would not be right to return a man’s goods to him (when he is in a drunken rage and intent on murder). What may be said about the particular rules that in a few cases do not hold, is that the reason and cause that they do not hold can be found in a HIGHER law or rule: It is conducive to the orderliness of the state to restore a man’s goods to him…but not if the man is planning to use them to overturn the state or to murder a man. In either case (whether to follow the detailed particular rule, or to disregard it) , due reason should be followed: usually, in pursuing the higher-order good by following the general rule, and sometimes (rarely) in pursuing the higher-order good, rather than the lower-order good that following the rule would achieve but at the expense of the higher.

Now, some want to use the above passage in AL to claim that in some irregular situations, a man and woman may CORRECTLY decide that “adultery is usually wrong, but in THIS case it is the better path, and therefore we ought to continue in it.” What they cannot do, however, is CORRECTLY tie such a conclusion to a higher-order good that must be preserved even though that requires disobeying the lower-order rule against adultery. Indeed, this sort of claim seems to be what Francis meant by his reference to Thomas. But while the PRINCIPLE is entirely valid that people can and should properly consider and act in the few situations where they have to break the existing lower-order rule in order to obey a higher-order good, the principle cannot be invoked for a species of act which is constituted by an object of the act which is INTRINSICALLY disordered. This is the clear and decisive teaching of Veritatis Splendor, #76-78. Acts which are of their very nature immoral because they have a disordered object of the act, cannot become moral acts under ANY intention or circumstance, and thus cannot be made out to be in conformity with a higher-ordered good. Never. Hence it is never the case that a person can rightly determine to disregard a lower-order rule in order to properly serve a higher order good by an intrinsically disordered act. The couple above are objectively wrong: the moral norm against adultery DOES hold in all places and times, and there are no special circumstances that justify a departure from the rule.

If Francis-supporter thinks that “many” or even “most” marriages are null, and that this justifies departure from the general standard against adultery “in detail” cases, this would itself prove that Thomas is being taken out of context because Thomas is clear that the kind of thing that makes for a departure is rare; and that it against JPII (who followed Thomas) in trying to hoist it in support of acts that are intrinsically disordered, to which there cannot even in principle be exceptions.

“ … the general principle holds for all but — they say it explicitly — as one moves to the particular, the question becomes diversified and many nuances arise without changing the principle.”

A problem here is in not explicitly noting the distinction between particular circumstances and particularized rules. The more particular a rule is, the less binding it becomes. When, on a freeway with a 55 mph speed limit, we are driving in traffic that is moving generally at 70 mph, we match our speed to the traffic. We thus give effect to the more general and more binding rule that we must drive at a safe speed, understanding that – as traffic engineers prove by their science and prudential drivers know intuitively – mixture of speeds, distinguished from speed itself, is the more fruitful source of highway collisions.

It is not, then, that particular circumstances allow us to set aside a principle, but that a rule affecting to be a particular instantiation of the principle may be insufficiently nuanced to apply the principle effectively in all diverse situations. One does not prescind from the general principle in order to make a particular rule for this diverse situation, but prescinds from a specifically particularized, unnuanced rule in order to give effect to the general principle.

IMHO, AL tries to do, or at least allows, the former, i.e., it contemplates in hard situations not prescinding from, but actually making a particular rule contravening the general principle that those who willingly continue in what they know the Church tells them is grave sin are not to be admitted to the Holy Communion.

AL is encouraging casuistry in a sense – a bad sense. A good casuistry is what any judge uses in the common law, finding paradigms in already decided cases and deciding on analogy to what appears to be the most similar case. This is not letting circumstance rule, because what is “most similar” can only be decided on some criteria appealing to general principles of law and justice. AL is bad casuistry because instead of letting general moral principle identify the paradigm for the particular, it encourages unprincipled distinctions to be made between the paradigm and the particular, thereby speciously justifying a self-serving result.

1. But our Holy Father has great difficulty kneeling!

2. Dear Father, please, PLEASE, p-l-e-a-s-e tell us where you got that eye-popping St Thomas Aquinas picture. Did you do that yourself?

[Someone texted it to me this morning. I think it is making the rounds.]

Prescinding from the elephant in the room, I’ll do my best, as a stupid layman and arm-chair Thomist, to explain what the Holy Father means in his remarks about Thomist morality.

The natural moral law does not operate in a vaccum, but rather within the context of human action. The reason for this is because, in their linguistic formulation, none of the precepts can account for every case; and thus in the realms of moral theology as well as in law there is a need for interpretation. As we know Our Lord interpreted the moral law on several occasions, enlarging, for example, the scope of the commandments against murder and adultery (Cf. Matt 5:21-22, 27-28).

It is true that there are intrinsic evils, such as theft and adultery, actions which are forbidden by negative precepts. Nonetheless, when evaluating the morality of any human act, it remains permissible to ask the question whether the action came within the prohibition.

Take stealing for example, a sin forbidden by the 6th Commandment. A necessary element of the sin of theft is that of mens rea, that is, the intention to steal another’s property. For this particular sin, it would be insufficient to simply examine the action and take note of the title to property. A man who walks off with another man’s briefcase, thinking it his own, is obviously not a thief. In an even more extreme case, St. Thomas would permit us to ask if the accused had an urgent need, for then, says the Angelic Doctor, “all things are common property, so that there would seem to be no sin in taking another’s property, for need has made it common” (II-II:66,7). What, therefore, appeared to the naked eye as theft was not theft upon further scrutiny, but rather (and we may speculate here) a good and necessary act for the preservation of life.

On the other hand, some sins, such as adultery, have both an objective element, which is intrinsically evil, and a subject element whose gravity and imputability depend entirely on the circumstances. A man who has sexual relations with a woman who is not his wife has surely committed adultery, objectively speaking, but according to the Schoolmen he would be completely innocent “if he had knowledge of another’s wife, thinking her his own” (ST, Supp 5 ad 4). How might this kind of excusable ignorance arise today? To give one obvious example, marriage tribunals are not infallible, and one could render an erroneous judgment.

Therefore, even with the negative precepts of the natural law, we may rightly assert with St. Thomas that it is “reductive simply to consider whether or not an individual’s actions correspond to a general law or rule, because that is not enough to discern and ensure full fidelity to God in the concrete life of a human being” (AL 304). And I would add that it is not only all those living in irregular situations that must be faithful to God, but we too in our discernment of others, and according to our state in life, so that we are not guilty of rash judgment.

Of course, as I said at the outset, this explanation doesn’t resolve the present debate over Holy Communion for the divorced and remarried. But I hope it does shed some light on it. One need not endorse a false “situation ethics” to uphold true Catholic morality.

” ‘St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure affirm that the general principle holds for all but — they say it explicitly — as one moves to the particular, the question becomes diversified and many nuances arise without changing the principle,” he had said. It is a method that was used for the Catechism of the Catholic Church [?] and “Amoris Laetitia,” he added.’ ”

I was going to do a long comment on this talk, but I am tired and so, I will limit things to merely giving the complete quote from St. Thomas, in context.

The quote is from the Summa Theologica, I.II Q 94 Art. 4:

Article 4. Whether the natural law is the same in all men?

On the contrary, Isidore says (Etym. v, 4): “The natural law is common to all nations.

I answer that, As stated above (Article 2,Article 3), to the natural law belongs those things to which a man is inclined naturally: and among these it is proper to man to be inclined to act according to reason. Now the process of reason is from the common to the proper, as stated in Phys. i. The speculative reason, however, is differently situated in this matter, from the practical reason. For, since the speculative reason is busied chiefly with the necessary things, which cannot be otherwise than they are, its proper conclusions, like the universal principles, contain the truth without fail. The practical reason, on the other hand, is busied with contingent matters, about which human actions are concerned: and consequently, although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects. Accordingly then in speculative matters truth is the same in all men, both as to principles and as to conclusions: although the truth is not known to all as regards the conclusions, but only as regards the principles which are called common notions. But in matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles: and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all.

It is therefore evident that, as regards the general principles whether of speculative or of practical reason, truth or rectitude is the same for all, and is equally known by all. As to the proper conclusions of the speculative reason, the truth is the same for all, but is not equally known to all: thus it is true for all that the three angles of a triangle are together equal to two right angles, although it is not known to all. But as to the proper conclusions of the practical reason, neither is the truth or rectitude the same for all, nor, where it is the same, is it equally known by all. Thus it is right and true for all to act according to reason: and from this principle it follows as a proper conclusion, that goods entrusted to another should be restored to their owner. Now this is true for the majority of cases: but it may happen in a particular case that it would be injurious, and therefore unreasonable, to restore goods held in trust; for instance, if they are claimed for the purpose of fighting against one’s country. And this principle will be found to fail the more, according as we descend further into detail, e.g. if one were to say that goods held in trust should be restored with such and such a guarantee, or in such and such a way; because the greater the number of conditions added, the greater the number of ways in which the principle may fail, so that it be not right to restore or not to restore.

Consequently we must say that the natural law, as to general principles, is the same for all, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge. But as to certain matters of detail, which are conclusions, as it were, of those general principles, it is the same for all in the majority of cases, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge; and yet in some few cases it may fail, both as to rectitude, by reason of certain obstacles (just as natures subject to generation and corruption fail in some few cases on account of some obstacle), and as to knowledge, since in some the reason is perverted by passion, or evil habit, or an evil disposition of nature; thus formerly, theft, although it is expressly contrary to the natural law, was not considered wrong among the Germans, as Julius Caesar relates (De Bello Gall. vi).

Aquinas, likewise, asks the question (from the same question, 94):

Article 5. Whether the natural law can be changed?

On the contrary, It is said in the Decretals (Dist. v): “The natural law dates from the creation of the rational creature. It does not vary according to time, but remains unchangeable.”

I answer that, A change in the natural law may be understood in two ways. First, by way of addition. In this sense nothing hinders the natural law from being changed: since many things for the benefit of human life have been added over and above the natural law, both by the Divine law and by human laws.

Secondly, a change in the natural law may be understood by way of subtraction, so that what previously was according to the natural law, ceases to be so. In this sense, the natural law is altogether unchangeable in its first principles: but in its secondary principles, which, as we have said (Article 4), are certain detailed proximate conclusions drawn from the first principles, the natural law is not changed so that what it prescribes be not right in most cases. But it may be changed in some particular cases of rare occurrence, through some special causes hindering the observance of such precepts, as stated above (Article 4).

What Aquinas does not discuss in this article is what he means by particular cases. It is here that one may see why the application of particular cases was never meant to be taken as a good by St. Thomas, merely an evil to be tolerated.

One may ask if particular instantiations of a law can lead to its exact opposite. This leads us into the distinction between universal laws and general laws. It is a long topic and I am too tired to comment on it, tonight.

The Chicken

How might this kind of excusable ignorance arise today? To give one obvious example, marriage tribunals are not infallible, and one could render an erroneous judgment.

Juris, it is true enough from your example that a man might have knowledge of another man’s wife erroneously.

But since nobody either in that situation or observing it imagines that the man would be wrong to approach the altar for communion, nor that the priest ought not give it to him (not least, because everyone else will have the same error). Hence it is not germane to the situations the Pope is talking about – which are the cases where the man actually grasps that what he is doing falls under the species of act “adultery”, and must decide whether to continue to commit adultery or not. If by Francis’s formulation this man is weighing whether ongoing adultery is

for now is the most generous response which can be given to God, and come to

see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the

concrete complexity of one’s limits, while yet not fully the objective ideal

then this has nothing to do with the kind of example you gave, where the man had erroneous “information”. Because of an intense and provocative ambiguity, the language in AL can theoretically be read in a way that conforms to irreformable doctrine, but it is easily read in a way not so conforming, implying that the man weighing adultery might rightly conclude that it is “the most generous response” that he can give to God.

Cherry-picking the writings of the Angelic Doctor is vice’s homage to virtue.

Fr. Z wrote:

“[I need a sound Thomist to help me out with that. It sounds as if the principle of non-contradiction is in play here, but I could be wrong. If a “general principle” can be turned 180° through nuances, then… is it a general principle?]”

I am short on time, at the moment. I might write a long reply later. This is not, specifically, a Thomistic question. St. Thomas did not discover this property of general laws. It was known to Aristotle. There are several sources, but there are two or three treatises that might be cited: 1) The Nicomachean Ethics, which discusses general rules and particular instantiations in a generic way. In a Book II, chapter 7, we read:

“1But it is not enough to make these general statements [about virtue and vice]: we must go on and apply them to particulars [i.e. to the several virtues and vices]. For in reasoning about matters of conduct general statements are too vague,* and do not convey so much truth as particular propositions. It is with particulars that conduct is concerned:† our statements, therefore, when applied to these particulars, should be found to hold good.”

2) The Organon and in particular, The Categories and Prior Analytics.

I am on the run right now, but as to the question whether or not a general rule can be turned 180 degrees on its head, the answer is, yes, depending on how general the rule is and to what it is applied. I would have to get into the guts of the theory to explain how it happens, but a simple example should demonstrate that it is possible:

General Principle: water puts out fires

Particular: triethylborane

Water will cause the fire to enlarge.

The reason has to do with the nature of composite objects and actions. More, later.

The Chicken

I am not one who thinks that AL is synonymous with the thought of Pope Francis. Rather it is a vehicle for a desire of his created by those so tasked for finding a way to make it so. After all, Pope Francis cannot (and also won’t in the case of the Dubia) explain it, and is always deferring to others to explain the reasoning. So there is some separation between the thought of Pope Francis and the thought of AL, even though their ends are the same.

When we look at the moral law, there tends to be two basic camps — moral law as minimums and moral law as maximums. It is pretty clear that Pope Francis sees the moral law as a maximum and there is a good chance that he sees it as a maximum that cannot be reached even with Grace, like Luther. However, the Catholic view is neither for rather the moral law is the life of Christ. It is not precept but person and to live the moral life is to live a life animated by the Spirit, in whom alone there is life as He is sustainer and consummator. A moral person is another Christ (an icon of Christ) as the person and Christ share the same Spirit.

The failure at the moral life, to use the in vogue language, is a failure to be accompanied by Christ and a failure to allow the indwelling of the Spirit. In the case of venial sin, it is a wound to that accompaniment. In the case of mortal sin, it is the abandonment of that accompaniment. Receiving Communion in the case of the latter is thus lie and sacrilege because said individual is in a state of refusing to be accompanied by the Lord. It is not a state of gray in which our Lord accompanies us, but a refusal of the individual, upon hearing the call written upon his heart, in the Law, or in the preaching of the Gospel, to accept the accompaniment of our Lord, which is free and easy given by Him.

To live the life of the Spirit and to progress in that spiritual life, one must “sin no more”. This is to leave behind the law of the flesh, not simply strive after a moral maximum or reach beyond a moral minimum. St. Paul is very clear on this — the Law for the Christian is no longer an external, but rather the indwelling of the Spirit so that Law is both live and person.

Pingback: SATVRDAY CATHOLICA EDITION | Big Pulpit

Old joke:

Two prelates petition the Pope to pray and smoke.

The diocesan one comes out of audience and tells the other he was denied. What did you ask for? I asked whether I could pray and smoke.

Next, the Jesuit goes in and comes out happy for he was given permission. What did you ask the Pope?, asked the diocesan prelate. The Jesuit said: I asked whether I could pray while smoking.

I have studied Thomism pretty intensively, through the licentiate level. In the disputed sections in particular the doctrine of AL is not Thomistic. Not least because Thomism doesn’t just mean Thomas but also Thomas’s major commentators, particularly in the Dominican and Carmelite orders, though the Jesuits put forward a number of major Thomists in the early twentieth century. Thomists hold to exceptionless moral norms.

It would have been better to argue that AL is Scotist, because Bl. John Duns Scotus taught that God could release one from the obligation to follow the last seven of the ten commandments. This is how he explains the sacrifice of Isaac etc. I would hold that Catholic morality has been further developed since the turn of the fourteenth century, but if you were trying to root AL’s problematic doctrine in a great Scholastic, you would have better luck with Scotus than with Thomas.

I get the sense our Holy Father doesn’t find theological precision very important or pastoral, though.

The picture is so great. Did not know it was St. Thomas. You should post it every time the subject of AL arises.