I always enjoy the updates from the Monks in Norcia, Italy. They’ve brought the beautiful Benedictine life back to the place of Benedict’s birth and they make great beer!

I always enjoy the updates from the Monks in Norcia, Italy. They’ve brought the beautiful Benedictine life back to the place of Benedict’s birth and they make great beer!

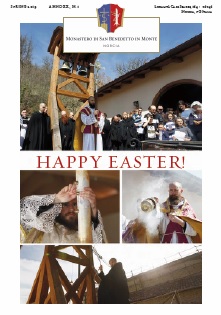

They sent out a newsletter with updates about their life. I could snip and cut and paste somethings, but you’ll do better to see for yourself. Take note especially of their photos of the Triduum! I also liked the photos of their new “protectors”, which have a lot of growing to do.

For the newsletter go HERE.

You can help yourselves and help the monks at the same time by “subscribing” to their beer!

The puppies are adorable. I’m not familiar with that particular breed, but there are various similar (and ancient) breeds of livestock guardian dogs from across Europe and central Asia. Remarkable animals; gentle giants but formidable when they need to be, with that guardian instinct embedded in them over centuries (possibly millennia) of living and working alongside humans and their herds.

I’m sure they’ll be a great asset to the community when they’ve grown up a bit!

Props for the Pre-55 Triduum pictures.

Excellent, there is news from Norcia. Remarkable photos of the Triduum (good to see Fr. Cassian Folsom along with the monks and faithful) and their trusty companions- the puppies.

Puppies are proof that God has a sense of humor. Proof that God loves us is, of course, baseball.

Two excerpts from the newsletter, the first about the monk’s annual visit to their Benedictine sisters at Norcia:

“Out in the courtyard again, we were graced with

hospitality, especially in the form of an abundant supply

of delicious homemade pizza. Taking a seat next to

Sister Benedetta, I asked her how their re-

establishment was going. “Slowly,” she said – or, as

they say here in Italy, “piano, piano” – but “patience is

the virtue of the strong.” She asked me what sort of

work I had been doing, and I told her about a rock

retaining wall that the novices are helping to build

behind our monastery. After a little more conversation

and a tasty piece of crostata baked by Sister

Benedetta herself, we rose to take our leave. Sister

offered me auguri, or good wishes, on building the

retaining wall, and I wished her auguri on rebuilding

their life in Norcia – that life centered around Our

Lord’s Presence. Piano, piano.”

As for the puppies, they will earn their daily bread and beer and be Good Doggies for the Lord:

“The Canticle of Daniel, the Benedicite, which we pray

at Lauds on Sunday mornings, is basically a prayer

commanding all living things to bless the Lord. So, in a

little way, by having dogs and directing them to protect

that part of Creation that is within our walls, as well

as to aid us in our lives as monks, we bear witness to a

restored Creation, which will only fully come to pass at

the consummation of the world.”

With our host’s permission, a few lengthy excerpts about St. Benedict and Western monasticism.

St. Benedict and his sister St. Scholastica were born in Nursia, Italy in the 5th century as the Roman Empire collapsed. His “Rule” for monks is a landmark document of the Catholic Church and Western civilization.

_____

From Thomas Woods “How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization”:

Early forms of monastic life are evident by the third century.

By then, individual Catholic women committed themselves as

consecrated virgins to lives of prayer and sacrifice, looking after the poor and the sick. Nuns come from these early traditions.

Another source of Christian monasticism is found in Saint Paul

of Thebes and more famously in Saint Anthony of Egypt (also

known as Saint Anthony of the Desert), whose life spanned the

mid-third century through the mid-fourth century. Saint

Anthony’s sister lived in a house of consecrated virgins. He

became a hermit, retreating to the deserts of Egypt for the sake of his own spiritual perfection, though his great example led thousands to flock to him.

The hermit’s characteristic feature was his retreat into remote

solitude, so that he might renounce worldly things and concen-

trate intensely on his spiritual life. Hermits typically lived alone or in groups of two or three, finding shelter in caves or simple huts and supporting themselves on what they could produce in their small fields or through such tasks as basket-making. The

lack of an authority to oversee their spiritual regimen led some of them to pursue unusual spiritual and penitential practices.

According to Monsignor Philip Hughes, an accomplished histo-

rian of the Catholic Church, “There were hermits who hardly

ever ate, or slept, others who stood without movement whole

weeks together, or who had themselves sealed up in tombs and

remained there for years, receiving only the least of poor nourishment through crevices in the masonry.”

Cenobitic monasticism (monks living together in monaster-

ies), the kind with which most people are familiar, developed in

part as a reaction against the life of the hermits and in recognition that men ought to live in community.

From Joseph Strayer and Dana Munro “The Middle Ages 395-1500”:

The great weakness of early monasticism had been its lack of discipline, which allowed individuals to go to extremes of idleness or asceticism. St. Benedict’s Rule [stated that] first, and most important, was the “work of God,” or prayer…Then the monastery was to be self-sufficient…Ordinary monks worked in the fields while those with special skills produced the manufactured goods which the brothers needed. If there were a surplus it might be sold outside the monastery at a price slightly lower than that asked by laymen who made similar wares…During their rest periods, especially in the afternoons, the monks were to spend their time in reading…The books which they read were usually on religious topics, but a few of the wealthier monasteries gradually acquired important collections of secular works. In this way some monasteries became important centers of learning, since, as Roman civilization continued to decline, few books survived outside monastic libraries [SG: Monks also hand-copied many books including classical works which would have disappeared under barbarian rule].

St. Benedict guarded against extreme asceticism just as he guarded against idleness, and made great allowance for human frailty. There were two meals a day…vegetables were allowed.

While the monks sought seclusion from the world and felt the chief service which they could render their fellow-men was to pray for their souls, they were bound to aid those who came to them for help. [SG: villages and markets often were founded near monasteries, trade routes and long-distance commerce eventually developed].

Every monk had to give up…selfish desires…pride. Some men could never conform to these standards; others needed a long period of initiation…a year’s probation was required before the novice was allowed to take the final vows.

From William Slattery “Heroism and Genius: How Catholic Priests Helped Build- And Can Help Rebuild- Western Civilization”:

The monastery, in order to be “a school for the Lord’s service,” was a community, a micro-state, self-sufficient and agrarian, with its chapel, refectory, dormitory, workshops, mill, garden, guesthouse, and library.

[SG: here Slattery quotes Newman] Silent men were observed about the country or discovered in the forest, digging, clearing and building; and other silent men, not seen, were sitting in the cold cloister, tiring their eyes and keeping their attention on the stretch, while they painfully copied and recopied the manuscripts which they had saved…by degrees the woody swamp became a hermitage, a religious house, a farm, an abbey, a village, a seminary, a school of learning and a city.

Briefly back to Thomas Woods:

In effect, whether it be the mining of salt, lead, iron, alum, or

gypsum, or metallurgy, quarrying marble, running cutler’s

shops and glassworks, or forging metal plates, also known as

firebacks, there was no activity at all in which the monks did

not display creativity and a fertile spirit of research. Utilizing their labor force, they instructed and trained it…[SG: I think it was monks who invented champagne after experimenting with double fermentation.]

From Christopher Dawson “Religion and the Rise of Western Culture”:

Thus, in an age of insecurity and disorder and barbarism, the Benedictine rule embodied an ideal of spiritual order and disciplined moral activity which made the monastery an oasis of peace in a world of war. It is true that the forces of barbarism were often too strong for it. Monte Cassino [SG: founded by St. Benedict] itself was destroyed by the Lombards about 581 [SG: there were also later raids against monasteries across Europe by the Vikings and Muslims], and the monks were forced to take refuge in Rome.

But such catastrophes did not weaken the spirit of the Rule; on the contrary, they brought the Benedictines into closer relation with Rome and Pope Gregory the Great, through whom the Benedictines and the Rule acquired their apostolic mission to the barbarians in the West.

…though monasticism seems at first sight ill-adapted to withstand the material destructiveness of an age of lawlessness and war, it was an institution which possessed extraordinary recuperative power.

Two stories about monasticism, the first involving Charlemagne, the second from the 20th century.

Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard (d. 840) was educated in the monastery at Fulda, after which the Abbot sent Einhard to the Palace School of Charlemagne at Aachen.

Einhard wrote that Charlemagne was an enthusiastic patron of the monastery at St. Gall, had the habit of going to Lauds, and in Benedictine fashion enjoyed having a book read to him during meals- his favorite being St. Augustine’s City of God.

The second story is about Judge William Clark, from Paul Kengor’s biography “The Judge: Ronald Reagan’s Top Hand” (the Wikipedia entry on Clark is best ignored).

Clark was a Californian from a ranch family. Around 1950 as a young man, just before or after his military service, he entered a monastery. He left after eight months when he realized he did not have a vocation.

In California in the 1960s as a judge (he came from a line of lawmen/ranchers) he became friends with Governor Ronald Reagan, also an avid horseman.

Later, as President, Reagan relied on Clark’s calm, professional demeanor and faith. Reagan appointed Clark as Deputy Secretary of State to balance the Secretary of State, former general Al Haig. Then after a year or so Reagan, ramping up his struggle against the Communists and allying with St. John Paul II, promoted Clark to National Security Advisor.

After a year or two Reagan asked Clark, a strong conservationist, to be Secretary of Interior and replace James Watt. Clark, during his first Christmas as Secretary of the Interior, invited leftist and militant environmentalists to his Department’s Christmas Party. Some actually showed up, expressing their surprise and thanks to Clark as, if I remember the story right, no one, Democrat or Republican, had ever invited them before.

Sometimes Secretary Clark, there is a photo in Kengor’s book, would ride a horse along Rock Creek Parkway in DC to his office at Interior.

Clark finally returned to his California ranch. In 1990 or so he survived a crash when he was piloting his small plane. To thank the Lord, he built a chapel atop a hill on his ranch. Clark died in 2013. Last I heard, there is an annual Mozart Festival at his chapel atop the hill.

One never knows what a few months at a monastery can lead to. Except, of course, the Lord.

Quaerere Deum.