QUAERITUR:

Father,

In John 20:22-24, it says “And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.'”

I’m interested in knowing the limits of this authority.

For example, it seems clear to me that they were not authorized to forgive the sins of the unrepentent, [A key point.] and I ask you to consider that a “given” in the rest of this discussion. God will not be made a fool.

We know that venial sins can be forgiven without confession, through various other pious works.

We know that baptism forgives all sins, including mortal sins, committed up to that point. And that the Sacrament of the Sick forgives venial sins (and, as I recall, mortal sins if the patient is not able to confess, and would have confessed if he were able).

We also know that the ordinary way mortal sins are forgiven is through the reception of absolution in a confession in which the penitent orally confesses all his mortal sins, in number and kind, to a priest who has faculties to hear the confession.

We also know that under certain extreme circumstances (e.g., a sinking ship or an airplane about to crash) a priest can validly absolve even mortal sins with a general absolution (abuses of this practice notwithstanding).

We also know that a priest must have faculties to absolve to be able to do so validly. These faculties can be extended or denied to persons, geographical territories, or even to particular sins (e.g., abortion).

We also know that any priest, even a laicized or apostate priest, can validly absolve a penitent in danger of death.

The Church also has at least some authority to define certain things as sins in one time or place and not another (e.g., Holy Days of Obligation, fasting and abstinence).

It is also my understanding that in the early church the practice of confession did not take the form it has today, although I don’t know what the differences were.

So we see that this authority can be exercised, changed, or denied through human law or decree (e.g., faculties, the specific form confession takes, etc.)

My question is this:[Whew!] What are the limits of the Church’s authority to bind and loose mortal sins? Could, for example, the Church make penance services, with general absolution and no individual oral confession of sins to a priest, the ordinary way mortal sins are forgiven? If so, how far could the Church go in this direction?

I’m not asking about what would or would not be a good idea from a pastoral point of view. I’m only asking about validity.

Thank you for all the great work you do!

Firstly, that was a pretty good summary you gave. I am pleased to post it, because it could be instructive for others.

In the antepenultimate, you move too quickly from the “limits of the Church’s authority to bind and loose” to the manner in which that is enacted.

The Church’s authority to forgive sins is pretty much unbounded, but with one provision that you brought up. The penitent must be penitent. That is, the person whose sins are to be forgiven must truly be sorry for those sins with either attrition or contrition. No repentance and sorrow, no absolution.

There is no sin that is so great that it cannot be forgiven. So, the Church’s authority has no bounds in that respect. Also, the Church determines how sacraments are celebrated. So, the Church is free in that respect. However, sacraments have their proper nature and that nature must be respected. The Church is necessarily bound in by the nature of the sacrament itself.

The manner of celebration of sacraments is determined by the Church. Hence, all the sacraments have undergone changes in their rites over the centuries. However, the essence of the sacraments have not changed. Holy Church teaches that sacraments have both matter and form. With most sacraments there is a material matter (the bread and wine, the water, the oil) and form (the words prescribed by the Church). The matter can vary (the West uses unleavened bread and the East leavened) and the form can vary (the form for Confirmation changed after the Council, and both the pre-Conciliar and post-Conciliar are valid). What can’t change is that there must by BOTH matter AND form.

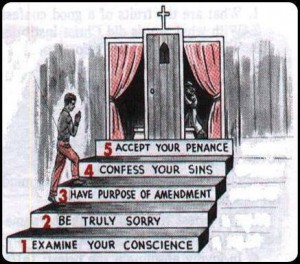

The Church teaches at Trent, along the lines of St. Thomas, that the matter of the sacrament of penance is comprised of the acts of the penitent, including sorrow, confession of sins, atonement or desire for atonement. In the case of this sacrament, that matter is sometimes called quasi-matter rather than just matter because the acts of the penitent (sorrow, confession, desire for atonement) aren’t material substances (water, oil, wine, bread). There are those who hold that this quasi-matter is necessary for the completeness of the sacrament, as a kind of pre-condition, but not necessarily its essence. That is to say that, because the acts of the penitent are not themselves the causes of grace in the soul, the priest by his absolution is the sole administrator of the sacrament. Hence, the unconscious can be validly absolved, even though they are not themselves acting to provide the quasi-matter.

In fact, there are times when it is impossible for a person to act, to express outwardly sorrow, confession and purpose of amendment. Physical impossibility allows for absolution without the quasi-material completeness of confession of sins, etc. Hence, when in the moment that absolution must be given, the material, outward confession is not complete (the penitent can’t confess, the penitent has sincerely forgotten some sins, the penitent confesses sins that are already forgiven and therefore gone, etc.) those sin are nevertheless absolved, though indirectly so, rather than directly. And something is left incomplete, even though absolution was validly given.

There remains a duty to confess all sins, to bring completeness to the sacrament. That is why in the case of “general absolution” the penitents (conscious or unconscious) have an obligation, as soon as possible, to make a regular, good confession of all mortal sins in kind and number.

Could the Church determine that the ordinary way of receiving the sacrament of penance would be through communal services lacking any outward confession of sins, expression of sorrow, etc.? One might argue that, by the fact that they are there, the people seeking the sacrament are showing some sorrow, etc., which could be sufficient. Also, in the ancient Church, even when there was public confession of sins, a distinction was made about those sins which, because of their nature, had to remain secret and those which had to be revealed. Therefore, it seems possible that there can be communal penance services in which there is no open confession, profession, etc., with valid absolution. And the Church has those, according to the law, etc. However, again and again the Church affirms that penitents are, thereafter, strictly obliged to make an auricular confession of sins as soon as opportunity affords.

Keep in mind also that, over the centuries, we understand a great deal more about sacraments and the sacrament of penance than our forebears did in the ancient Church. Certain practices dropped away as our knowledge and wisdom developed. That’s why certain practices that were once valid are not done now: we found better ways, better rites, to express the inward, sacramental reality. We are our rites.

Could the Church lay down that communal services are the ordinary way to receive the sacrament? No, I don’t think so, because of the nature of sacraments as having matter and form. We don’t allow that the minimum required for validity is the ordinary way sacraments are administered because the complete celebration of the sacrament is important ad integritatem. We don’t just walk into church and have Father say, “This is my body”, etc. over bread and wine, then receive it and walk out. We don’t just pour water with the words and baptize without everything else, except in cases of emergency. And, in the case of emergency baptism, the person was then to go through at a later time the rest of the rites that were omitted! Communal penance without confession and expression of sorrow and amendment, is like the 30 second consecration of bread and wine and communion (valid consecration but horrifying because it is outside of Mass).

Emergency conditions which reveal the minimal for validity don’t provide a good foundation for ordinary practice.

The matter (quasi-matter) of the sacrament of penance must be respected.

In any event, I hope that clear up that question.

And since it is Saturday…

GO TO CONFESSION!

I’m glad that this question was submitted. I’ve actually spent a lot of time wondering the same thing, since my scrupulosity often turns what should be a very simple confession into an extremely agonizing affair for me. To take this a step further, what if the Church were to implement a practice similar to that of the Armenian Orthodox, where a prayer of general confession admitting to each of the 7 deadly sins is recited by the faithful together during the Liturgy, and the priest then says the words of absolution over everyone at once? I have read many Armenian Orthodox Christians who confirm that this is the only way that penance is administered in most instances. I’ve wondered if this would be considered valid, since there is a limited sort of confession involved, or if these Armenian Christians are going to their judgements unabsolved due to a defect in form. I’m fairly sure that Trent states that sins cannot be confessed in a general way, though I don’t know if this is dogmatic or disciplinary in nature.

Instead of a communal service WITHOUT individual confession, what if, as the church becomes smaller and poorer, we return to the early church practice of confessing our sins in public?

At the Eschaton, we’re all going to simultaneously know everyone else’s sins as part of our mind-blowing initiation into the life of God, so why not start now?

Perhaps such a schema would have an immediate effect on reducing habitual sin and offenses against one’s neighbor.

“Liber scriptus proferetur,

In quo totum continetur,

Unde mundus judicetur.”

. Group celebration of the sacrament of penance in one of several different ways, authorized by Pope Paul VI in 1973.One form has a communal penitential service, with individual confession of sins with absolution. Another form is entirely communal, including general absolution. When general absolution is given in exceptional circumstances, the penitents are obliged to make a private confession of their grave sins, unless it is morally impossible, at least within a year. In many places, especially in North America, communal confession is administered as a substitute to the regular Sacrament of Confession on a regular basis, even on a weekly basis, the priest and Parish Council both failing to educate the faithful on the legality of the matter. No one is told that, in order for the communion confession to be valid, each individual MUST receive the regular Sacrament of Confession on a one to one basis with the priest as has been the Catholic practice for centuries. And the believer CANNOT receive the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist if he/she is in a state of mortal sin and has not received the Sacrament of Confession after having once received a Communal Confession. You cannot receive two Communal Confessions in a row without a proper confession.