Today’s first entry in the Martyrologium Romanum says:

Today’s first entry in the Martyrologium Romanum says:

1. Memoria sancti Ambrisii, episcopi Mediolanensis et Ecclesiae doctoris, qui pridie Nonas aprilis in Domino obdormivit, sed hac die potissimum colitur, qua celebrem sedem adhuc catechumenus gubernandam suscepit, cum civitatis praefecturae officio fungebatur. Verus pastor et doctor fidelium, maxime in omnes caritatem exercuit, libertatem Ecclesiae ac rectae fidei doctrinam adversus arianos strenue defendit et commentariis hymnisque concinendis populum pie catechizavit.

How about you readers providing your own flawless yet elegant rendering?

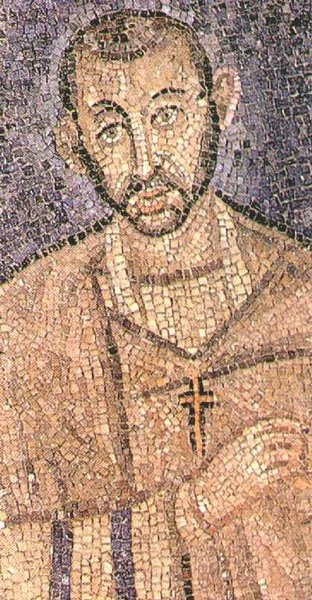

St. Ambrose of Milan (+4 April 397), a titanic figure of the late 4th century who changed the shape of Church and State relations for a thousand years, who brought much of the wisdom of Greek writings to the West, and who helped to bring St. Augustine of Hippo into the fold.

Would that we might see his like again in the great capitals of the world.

There are too many interesting things about Ambrose for them all to be shared here, but we have space for a couple.

There is a famous moment recounted by St. Augustine in his Confessions (Bk VI) about visiting St. Ambrose.

Augustine walked into the room where Ambrose was sitting and saw him staring at a book! Ambrose was reading and not even moving his lips!

Augustine was so impressed by this that slipped silently out of the room without saying anything to Ambrose, lest he disturb him.

Augustine was very impressed by Ambrose and had wanted to talk to him about various problems and doubts. Because of all the people pressing around Ambrose, who was tremendously important and sought after, Augustine was never able to get near him in public.

Let’s read the text and hear about it from Augustine himself!

Remember, at this point Augustine is a hot property in Milan and not yet Christian, though interiorly twisting on the spikes of difficult doubts and problems.

Augustine wasn’t really praying yet and he he still was considering things in very worldly terms.

6,3. Nor had I come yet to groan in my prayers that thou wouldst help me. My mind was wholly intent on knowledge and eager for disputation. Ambrose himself I esteemed a happy man, as the world counted happiness, because great personages held him in honor. Only his celibacy appeared to me a painful burden. [Augustine was not chaste at the time and he was angling for a politically favorable marriage.] But what hope he cherished, what struggles he had against the temptations that beset his high station, what solace in adversity, and what savory joys thy bread possessed for the hidden mouth of his heart when feeding on it, I could neither conjecture nor experience.

Nor did [Ambrose] know my own frustrations, nor the pit of my danger. For I could not request of him what I wanted as I wanted it, because I was debarred from hearing and speaking to him by crowds of busy people to whose infirmities he devoted himself. And when he was not engaged with them—which was never for long at a time—he was either refreshing his body with necessary food or his mind with reading.

Now, as he read, his eyes glanced over the pages and his heart searched out the sense, but his voice and tongue were silent. Often when we came to his room—for no one was forbidden to enter, nor was it his custom that the arrival of visitors should be announced to him—we would see him thus reading to himself. After we had sat for a long time in silence—for who would dare interrupt one so intent?—we would then depart, realizing that he was unwilling to be distracted in the little time he could gain for the recruiting of his mind, free from the clamor of other men’s business. Perhaps he was fearful lest, if the author he was studying should express himself vaguely, some doubtful and attentive hearer would ask him to expound it or discuss some of the more abstruse questions, so that he could not get over as much material as he wished, if his time was occupied with others. And even a truer reason for his reading to himself might have been the care for preserving his voice, which was very easily weakened. Whatever his motive was in so doing, it was doubtless, in such a man, a good one.

Amazing stuff there.

Keep in mind that, i the ancient world, books were rare. If you had a book, you were probably wealthy. If you got your hands on a book, you had to remember what you read because you might not ever see that particular book again. There would be public readings of books so that more people could hear them. People had to read aloud, actually, to help their memory. The more senses you could involve, the easier it was to remember the material. This holds true today! But, in the ancient world, everyone who read, read aloud.

Notice that Augustine, writing many years after the scene he recounts, and now a bishops himself, understands what it is to be entirely lacking in free time. He wonders if Ambrose read quietly so that the intellectually hungry people around him wouldn’t ask him to explain what he was reading, thus cutting short his own time for study. Also, Augustine himself later in life suffered from having a very weakened voice. In his sermons we acutally here him saying once in a while to the crowd that they had to stop making so much noice in their reactions to him, because his voice to too weak to shout over them! At any rate, Augustine puts a positive spin on what Ambrose did.

Busy tired clergymen understand each other.

If Augustine had a lot of admiration for Ambrose, the famously irascible Jerome did not.

My conjecture is that Jerome was jealous of Ambrose, who had "made it" in the Church in Italy, whereas Jerome always played second fiddle. But I digress.

What’s with Jerome and Ambrose? Well, to get at this we have to bring in a third character, Tyrannius Rufinus of Aquileia.

You are no doubt aware that Jerome and his old friend of his youth Rufinus (+410) had a titanic clash over the writings and teachings of the early Alexandrian exegete Origen. When they were young, they were very close, forming part of a group of dedicated Christians at Aquileia and then later at Jerusalem. They began to argue over the theology of Origen, but they patched things together before Rufinus left Palestine for Italy.

You are no doubt aware that Jerome and his old friend of his youth Rufinus (+410) had a titanic clash over the writings and teachings of the early Alexandrian exegete Origen. When they were young, they were very close, forming part of a group of dedicated Christians at Aquileia and then later at Jerusalem. They began to argue over the theology of Origen, but they patched things together before Rufinus left Palestine for Italy.

However, once in Italy Rufinus began to translate Origen Peri archon (De principiis). In his preface Rufinus made the mistake of assuming that just because Jerome had translated some of Origen’s work, therefore Jerome was a fan of Origen. People around Jerome also thought Rufinus purposely made Origen sound more orthodox than he was. These folks wrote to Jerome to let him know what they thought Rufinus was up to and asked Jerome to explain what was going on. In response Jerome translated Origen himself. In a letter he strongly denied being a partisan of Origen’s theology, even though he admired Origen’s skill. Jerome focused his laser on Origen’s statements about the resurrection and the preexistence of souls, and how the Persons of the Trinity related to each other which made him sound like a subordinationist. Jerome, in this second phase of translation, interpreted Origen in a very strict and harsh way.

When you look at the way Jerome spoke of Origen the first time around, 12 years before, and what he did to him in the second round, it is pretty clear that this was a reaction to Rufinus’s written assumption about Jerome. Jerome was afraid that his own reputation was going to be damaged by a positive association with ideas which seemed very strange to many people, especially in the West. In short, he turned savagely on both Origen and Rufinus in order to defend his reputation. In defending himself Jerome was a little less than sincere.

When you look at the way Jerome spoke of Origen the first time around, 12 years before, and what he did to him in the second round, it is pretty clear that this was a reaction to Rufinus’s written assumption about Jerome. Jerome was afraid that his own reputation was going to be damaged by a positive association with ideas which seemed very strange to many people, especially in the West. In short, he turned savagely on both Origen and Rufinus in order to defend his reputation. In defending himself Jerome was a little less than sincere.

Rufinus responded, of course. He had too. Rufinus pointed out, for example, that in a commentary on Ephesians Jerome had referred without objection to ideas of Origen about the preexistence and fall of souls into bodies. There are other points as well. Jerome responded with vitrolic force saying that some people (e.g., Rufinus), "love me so well that they cannot be heretics without me."

Of course the ways of saints are strange and fraught with problems. The postal service, or lack of one, actually plays an importance role in all of this. Jerome wrote a friendly letter to Rufinus assuring him of his high esteem and speaking of their past friendship and the passing of his mother. He expressed his desire to avoid a public fight.

The letter never reached Rufinus. Jerome’s friend Pammachius kept it, and published instead a letter of Jerome which accompanied his translation of Origen’s De principiis. Not having seen Jerome’s irenic gesture, Rufinus published his Apology, in response to Jerome the attacker.

In Book II of his Apology, Rufinus points out how Jerome had attacked Ambrose. He mentions, as a matter of fact, Ambrose’ work De Spiritu Sancto. Thus, Rufinus about Jerome’s view of Ambrose. Rufinus relates more of Jerome’s disdain for his "rival" in Milan (Apology 2,23-25) as he digs into accusations of plagiarism which were being hurled around. Rufinus says in 2, 23 that Jerome referred to Ambrose as a raven, a bird of ill omen, croaking and ridiculing in an strange way the color of all the others birds on account of his own total blackness… "praesertim cum a sinistro oscinem corvum audiam croccientem et mirum in modum de cunctarum avium ridere coloribus, cum totus ipse tenebrosus sit."

In Book II of his Apology, Rufinus points out how Jerome had attacked Ambrose. He mentions, as a matter of fact, Ambrose’ work De Spiritu Sancto. Thus, Rufinus about Jerome’s view of Ambrose. Rufinus relates more of Jerome’s disdain for his "rival" in Milan (Apology 2,23-25) as he digs into accusations of plagiarism which were being hurled around. Rufinus says in 2, 23 that Jerome referred to Ambrose as a raven, a bird of ill omen, croaking and ridiculing in an strange way the color of all the others birds on account of his own total blackness… "praesertim cum a sinistro oscinem corvum audiam croccientem et mirum in modum de cunctarum avium ridere coloribus, cum totus ipse tenebrosus sit."

Again, going on about Jerome’s accusation against Ambrose of plagiarism, in 2,25 Rufinus continues about Jerome’s treatment of Ambrose with his own counter charges:

25. You observe how (Jerome) treats Ambrose. First, he calls him a crow and says that he is black all over; then he calls him a jackdaw who decks himself in other birds’ showy feathers; and then he rends him with his foul abuse, and declares that there is nothing manly in a man whom God has singled out to be the glory of the churches of Christ, who has spoken of the testimonies of the Lord even in the sight of persecuting kings and has not been alarmed. The saintly Ambrose wrote his book on the Holy Spirit not in words only but with his own blood; for he offered his life-blood to his persecutors, and shed it within himself, although God preserved his life for future labours.

Suppose that (Ambrose) did follow some of the Greek writers belonging to our Catholic body, and borrowed something from their writings, it should hardly have been the first thought in your mind, (still less the object of such zealous efforts as to make you set to work to translate the work of Didymus on the Holy Spirit,) to blaze abroad what you call his plagiarisms, which were very possibly the result of a literary necessity when he had to reply at once to some ravings of the heretics. Is this the fairness of a Christian?

Is it thus that we are to observe the injunction of the Apostle, “Do nothing through faction or through vain glory”? But I might turn the tables on you and ask, Thou that sayest that a man should not steal, dost thou steal?

I might quote a fact I have already mentioned, namely, that, a little before you wrote your commentary on Micah, you had been accused of plagiarizing from Origen. And you did not deny it, but said: “What they bring against me in violent abuse I accept as the highest praise; for I wish to imitate the man whom we and all who are wise admire.” Your plagiarisms redound to your highest praise; those of others make them crows and jackdaws in your estimation. If you act rightly in imitating Origen whom you call second only to the Apostles, why do you sharply attack another for following Didymus, whom nevertheless you point to by name as a Prophet and an apostolic man?

For myself I must not complain, since you abuse us all alike. First you do not spare Ambrose, great and highly esteemed as he was; then the man of whom you write that he was second only to the Apostles, and that all the wise admire him, and whom you have praised up to the skies a thousand times over, not as you say in two, but in innumerable places, this man who was before an Apostle, you now turn round and make a heretic.

Thirdly, this very Didymus whom you designate the Seer-Prophet, who has the eye of the bride in the Song of Songs, and whom you call according to the meaning of his name an Apostolic man, you now on the other hand criminate as a perverse teacher, and separate him off with what you call your censor’s rod, into the communion of heretics. I do not know whence you received this rod. I know that Christ once gave the keys to Peter: but what spirit it is who now dispenses these censors’ rods, it is for you to say. However, if you condemn all those I have mentioned with the same mouth with which you once praised them, I who in comparison of them am but like a flea, must not complain, I repeat, if now you tear me to pieces, though once you praised me, and in your Chronicle equalled me to Florentius and Bonosus for the nobleness, as you said, of my life.

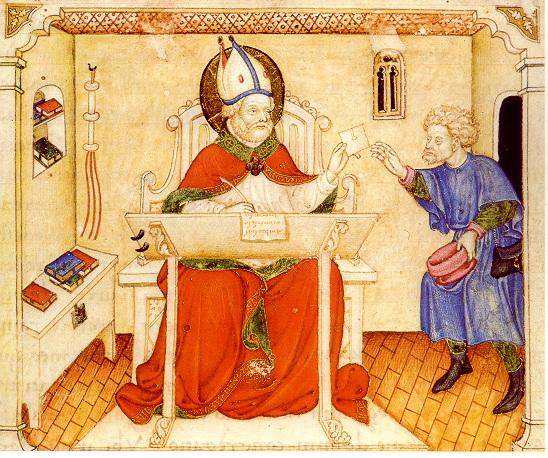

And from Jerome’s own pen we have this vicious attack on Ambrose (ep. 69,9). Jerome was writing in the year of Ambrose’ death, 397, to a Roman named Oceanus who wanted Jerome to help him fight against a bishop in Spain who had married a second time. Jerome tells Oceanus to drop it, since that bishops’ first marriage had been before baptism. However, Jerome uses the occasion to take a somewhat less than oblique swipe at Ambrose. Ambrose had been popularly proclaimed bishop in Milan in 374 even though he had not even been baptized and had no theological training. The emperor, who wanted peace, acceded and within a week Ambrose was baptized and consecrated bishop.

Jerome, who had probably been disappointed that he hadn’t been made bishop of Rome, surely felt the sting of this meteoric rise of Ambrose.

In any event, listen to Jerome:

One who was yesterday a catechumen is today a bishop; one who was yesterday in the amphitheater is today in the church; one who spent the evening in the circus stands in the morning at the altar: one who a little while ago was a patron of actors is now a dedicator of virgins. Was the apostle ignorant of our shifts and subterfuges? Did he know nothing of our foolish arguments? (Heri catechumenus, hodie pontifex; heri in amphitheatro, hodie in ecclesia; uespere in circo, mane in altari; dudum fautor strionum, nunc uirginum consecrator: num ignorabat apostolus tergiuersationes nostras et argumentorum ineptias nesciebat?)

Okaayyyy! That’s a big "NO!" vote from Jerome.

Regardless, today is the feast of St. Ambrose, who seemed to bring out both the worst and the best in people.

I am happy to have the company of Ambrose in a special way. I have a first class relic of the great saint and doctor in the chapel:

Is it thus that we are to observe the injunction of the Apostle, “Do nothing through faction or through vain glory”? But I might turn the tables on you and ask, Thou that sayest that a man should not steal, dost thou steal?

Is it thus that we are to observe the injunction of the Apostle, “Do nothing through faction or through vain glory”? But I might turn the tables on you and ask, Thou that sayest that a man should not steal, dost thou steal?

Very very cool.

Did Jerome or Rufinus have anything to say about +Trautman or +Tobin or Congressman Kennedy? [Can you imagine what Ambrose would have said to Kennedy?]

The more things change, the more they stay the same! 1500 years from now people will be reading about the personalities of our time. I wonder how the story will be written…

The memorial of St. Ambrose, bishop of Milan and doctor of the Church. He passed away on the eighth of April, but is venerated on this day, on which he took up governing the well-known see though he had not been baptized. He also held the office of city prefect. A true pastor and teacher of the faith, he exercised the greatest charity in all matters, and stoutly defended the Church’s liberty and true doctrine against the Arians. He piously instructed the people with commentary and hymns he had composed.

Fr. Z,

“S. Ambrosii ECD”.

ECD? “Ecclesiae Catholicae Doctor”?

Too bad you left out Jerome’s caustic mention of Ambrose in “de viris illustribus”. That one’s a beaut!

Clearly being a saint is not the same thing as having no defects!

Ahh…Saint Jerome, genius, polyglot, learned in the Scriptures, and grouch extraordinaire. One of my favorite saints. A priest I met in graduate school liked to say that, if Jerome could be declared a saint, there was hope for him in his own acerbity.

Wow, I didn’t know anything about this disagreement between these Great Men. Thanks for edifying us, Fr. Z!

If I may ask, what is the primary relic contained in that display?

ECD = Bishop, Confessor, Doctor

A marvelous post. Thank you.

I’m reminded of St.Francis de Sales words on patience:

I was unaware of the details of these disputes between St. Jerome and Rufinus. Fascinating. Thanks for providing it.

I have had an interest in patristics for a while. My own “nom de blog,” Melania, is taken from two women of that era, St. Melania the Elder and her granddaughter, St. Melania the Younger. Between the two of them, they knew St. Jerome, Rufinus, St. Augustine and many other great figures of that era.

St. Melania the Elder was once highly praised by St. Jerome but then her support of Rufinus, I believe, later drew his considerable and very articulate wrath. I believe he made puns on her name which means “black” so she ended up being compared to a black crow, raven, jackdaw, etc. along with the estimable St. Ambrose.

Lots of drama back in those days, … as there is now.

I’ve always liked St. Jerome. Brilliant and logical–he knew what he did mattered, and it did.

So much for the sticky sweet political correctness of contemporary Catholicism, which avoids truth at all costs, eh?

I love St. Ambrose! He was good and kind to St. Monica, a good woman but someone that priests used to cross the street to avoid. He guided her son, Augustine. And didn’t he coin the phrase, “When in Rome, do as the Romans?”

St. Ambrose is my confirmation saint (when I converted). So, happy St. Ambrose Day to all.

As Kipling has one of his characters say in a short story, “My brother knows it is not easy to be a Chief.”

I love reading those old letters! They were a bunch of characters, just like great (and ordinary) men of today.

I remember being taught in public school that St. Augustine was a nasty man who didn’t like women and invented original sin, while St. Jerome taught women and didn’t believe in original sin. It was only years later that I found out this was, shall we say, a little skewed… although, in the defense of whoever wrote the textbook, it was a long time ago and what I took from it might not have been exactly what it said. Anyway, it was still later that I discovered how both of them attacked each other for years. Somehow I find that endearing. They were so VERY nasty, and a certain sort of intellect delights in being nasty.

Was it Chesterton who said there is no one kind of saint, but that God can make any kind of man a saint? Despite nasty attacks on others, they were both great saints. And St. Ambrose too, of course. I love that story about him being made the bishop before he was baptized.

FInally, another tidbit about reading and writing. Augustine’s amazement at Ambrose’s silent reading isn’t proof that people commonly read to themeselves out loud in the ancient world, but it’s a clue that that might have been so. As a writer I was surprised to find that writers at the time composed out loud, something like newspaper reporters in the 1920s composed out loud as they phoned in their stories. In the ancient world, secretaries wrote everything down for authors. Having written professionally for a brief time before the computer became omnipresent, I used to compose a lot more in my head because it was a pain in the neck to revise and retype everything. Now most writers compose as they type because it is so easy to change things as many times as you like. Your thoughts don’t need to be as ordered when you start to write. I imagine that in patristic times, they were quite clear on what they wanted to say before they started to dictate.

Excerptio et traductio epistulae S. Hieronymi meum principium probant, ut lingua latina una sententia anglica tres loquetur. Rebus rhetoricis, S. Hieronymus cum Cicerone stet meo opinione.

Obvigilate corvos!

Salutationes omnibus.

I tend to use St. Jerome as an example of a saint who, at times, was, shall we say, less than tender to his enemies (real or perceived)! (The other example I like to use is St. Cyril of Alexandria!)

At Mass yesterday, our pastor talked about St. Ambrose in his homily. First he gave a short biography, and then discussed St. Ambrose’s defense of his basilica against Empress Justina, who was trying to take it over. St. Ambrose said that the church had a right to be independent. He then went on to talk about other saints who had defended the independence of church and state (and their separation), before mentioning that today, many people seem to have the idea that the separation of church and state means that religion should never have influence in the civil sphere, even when those in the civil sphere fail to uphold moral standards. This is absolutely wrong, he reminded us, and religious leaders absolutely have the right to admonish civil leaders when they step out of bounds. The homily stopped there, but it was fairly obvious why he chose to speak on that topic this week. I really liked his tie-in with St. Ambrose.

St. Ambrose was walking a fine line in defending his basilica; he had been civil prefect while bishop – a rare combination at any time. Naturally, the emperor would not have wanted divided loyalties, nor the Pope. Before the Church, “basilica” would have meant town hall, city hall or courthouse.

Jerome’s turn of phrase works on three levels: time, light/darkness and honor.

“Yestderday catechumen, today bishop (bridge builder, ‘pontifex’; yesterday at the ball game (amphitheaters were outdoor arenas, and yes, it’s modernized metonymy), today at church; last night at the track (with the same betting connotation as now), this morning at the altar; once promoter of (low-class) actors, today consecrator of virgins…”

Your post, and this memorial, brings back great memories of a pilgrimage where we visited the Basilica of St. Ambrose. Although it was raining like heck, it was cold and damp, the spiritual effect was overwhelming…we could not visit the baptismal font where he baptized St. Augustine but just venerating his relics with the martyrs Protase and Gervase and praying at the various altars (one for his brother Satyrus) was a very moving experience. He has become more real to me after being there and I thank you for posting these very inspirational meditations.

Memorial of Holy Ambrose, bishop of Milan and doctor of the Church, who before the ninth of April died in the Lord, but this day we celebrate, who though a catechumen accepted the governance of that celebrated see, where he held the office of prefecture of the city. A true pastor and faithful teacher, he exercised maximum charity, defended strenuously the liberty of the Church and the doctrine of the rule of faith and catechetized the pious people with commentaries he composed on the hymns.