WARNING BELOW…

Roman Station: St. Lawrence outside the walls

An examination of our conscience is a humbling experience. When we look to see who really are inside, we can have different reactions. Sometimes we find things which frighten and discourage us. If we are weak in our habits and our faith, that inveterate enemy of ours souls, the Devil who is “father of lies” will rub us raw with our ugliness tempting us to lose hope about the possibility of living a moral life or, in extreme cases, about our salvation.

On a less dramatic plane, falling down in our Lenten resolve on one day can cause a collapse of our will so that we will “flag” and give up.

This is why the Lenten discipline is so important. By it we learn to govern our appetites, examine our consciences, do penance, and learn the habits which are virtues. On the other hand, a recognition of sins and failures will “incline” us to call with humble confidence upon the mercy of God who paid the price for our salvation.

Today’s Collect taken from the ancient Gelasian Sacramentary for Saturday of the 4th week of Lent, has many Lenten elements and only a close look at the words can unlock what it really says.

COLLECT – LATIN TEXT (2002MR):

Deus, omnium misericordiarum et totius bonitatis auctor,

qui peccatorum remedia

in ieiuniis, orationibus et eleemosynis demonstrasti,

hanc humilitatis nostrae confessionem propitius intuere,

ut, qui inclinamur conscientia nostra,

tua semper misericordia sublevemur.

Misericordia means generally “tender-heartedness, pity, compassion, mercy”. In the plural, as we find it today, it refers to works of mercy. We find both a plural and a singular in today’s prayer and we must make a distinction between them. Our bulky and bountiful Lewis & Short Dictionary explains that bonitas is the “good quality of a thing” and also various benevolent and virtuous behaviors. When referring to a parent, bonitas means “parental love, tenderness.” Demonstro indicates, “to point out” as with the finger, “indicate, designate, show.” Demonstrasti is a “syncopated” form for demonstravisti, which helps the prayer to flow. The L&S states that inclino means, “to cause to lean, bend, incline, turn.” In a more neutral sense it signifies, “to bend, turn, incline, decline, sink.” By extension it means, “to decline, as in a fever, or sink down in troubles”, but it can also mean, more rarely, “to change, alter from its former condition”. We are all at sea with this word, so we turn to Souter’s A Glossary of Later Latin and find “to humble”. This is probably the direction we must go. Sublevo literally means to lift up from beneath, to raise up, hold up, support.” Thus it comes to mean also, to sustain, support, assist, encourage, console” and also, “to lighten, qualify, alleviate, mitigate, lessen an evil, to assuage.”

This word is in the beautiful 10th century Mozarabic Lenten hymn Attende, Domine often sung in parishes around the world even today: “Give heed, O Lord, and be merciful, for we have sinned against you. / To you, O high King, Redeemer of all, / we raise up (sublevamur) our eyes weeping:/ hear, O Christ, the prayers of those bent down begging.”

Confessio is from confiteor (con-fateor – the first word in our expression of sorrow for sins at the beginning of Mass). This is a complicated word. First, confessio is obviously “a confession or acknowledgment”. The Latin Vulgate (Heb 3:1) and St. Gregory the Great (+604 – Ep. 7,5) use it for “a creed, avowal of belief” in the sense of an acknowledgment of Christ. The most famous use of confessio, however, must be that of St. Augustine of Hippo (+430), whose stupendous autobiographical prayer is now known as Confessiones. The excellent Augustinus Lexicon now being developed says confessio has three major meanings: profession of faith in God, praise of God, and admission to God of sins. We can say “testify” or “give witness to.” Augustine uses the word testimonium twice in the second sentence of his Confessions. This is not “confession” in the sense of admission of criminal guilt, nor is it merely to a Christian confession of sins. Rather, it is a way of giving witness to the Christian character we put on in baptism, a witness by how we live to what the Lord has done within us. Sometimes that response requires humble admission of sins, sometimes it requires humbly giving glory to God. Sometimes it demands patient fidelity and the practice virtue in the tedium of everyday life. Sometimes it requires more spectacular deeds, even martyrdom. It always demands humility. The best confession we make is in our words and deeds, according to our state in life, in the midst of the circumstances we face each day no matter what they are.

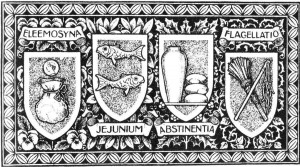

Our Collect reminds us of the remedies for sin identified by Jesus Himself: prayer, fasting (cf. Matthew 9:14), and almsgiving or works of mercy (cf. Matthew 6:1; Luke 12:33).

When Jesus cures the epileptic demoniac, He says that that sort of demon is driven out only by both prayer and fasting (Mark 9:27 Vulgate). In Acts 10 an angel tells the centurion Cornelius that his prayers and alms have been seen favorably by God (literally, they ascended as a memorial before God in the manner of a sacrifice).

St. Augustine said: “Do you wish your prayer to fly toward God? Make for it two wings: fasting and almsgiving” (En. ps. 42, 8).

In a Lenten Angelus address on 16 February 1997, St. John Paul II said:

The Church points out to us a path (of moving from a superficial life to deep interiority, from selfishness to love, of striving to live according to the model of Christ himself, that) … can be summarized in three words: prayer, fasting, almsgiving. Prayer can have many expressions, personal and communal. But we must above all live its essence, listening to God who speaks to us, conversing with us as children in a “face to face” dialogue filled with trust and love. In addition to being an external practice, fasting, which consists in the moderation of food and life-style, is a sincere effort to remove from our hearts all that is the result of sin and inclines us to evil. Almsgiving, far from being reduced to an occasional offering of money, means assuming an attitude of sharing and acceptance. We only need to “open our eyes” to see beside us so many brothers and sisters who are suffering materially and spiritually. Thus Lent is a forceful invitation to solidarity.

This brings us to conscientia. Conscientia signifies in the first place, “a knowing of a thing together with another person, joint knowledge, consciousness”. Note the unity, or solidarity, of knowledge in the prefix con-. It also means, “conscientiousness” in the sense of knowledge or feelings about a thing. It also has a moral meaning also as, “a consciousness of right or wrong, the moral sense”.

LITERAL TRANSLATION:

O God, author of all acts of mercy and all goodness,

who in fasts, prayers, and acts of almsgiving indicated the remedies of sins,

look propitiously on this testimony of our humility,

so that we who are being humbled in our conscience

may always be consoled by your mercy.

Remember, words have different meanings, which I why I provide raw vocabulary.

I must point out something that could change this literal translation.

St. Augustine in one of his sermons speaks of the mercy of God. Using the example of Jesus’ mercy to the woman caught in adultery (John 8), Augustine says – as if Jesus were talking – “Those others were restrained by conscience (conscientia) from punishing, mercy moves (inclinat misericordia) me to help you (ad subveniendum)” (s. 13.5 – 27 May 418 on the feast of St. Cyprian of Carthage). Even though in the Collect inclino is paired with conscientia rather than misericordia as it is in the sermon, the vocabulary suggests that this sermon may have been a partial source for this ancient Collect. This could provide a clue as to how to translate it. So, we can say “we who are being moved by our conscience” or even “we who are being brought low, bent down, humbled by our conscience” or “we who are flagging (as if under a weight) in our conscience”.

What to do? When translating we have to make a choice. This time around I chose “being humbled”.

As a people united before Christ’s altar of sacrifice, humbled and cast down low, we raise our eyes upwards to the Father who tenderly sees our efforts. But we can become weary in the midst of our Lenten discipline and the enemy is tirelessly working for our defeat.

Do not forget the military imagery of exercises and discipline we had in previous weeks.

In today’s Collect we beg Him to pick us back up, dust us off, and help us stay upright for the rest of the hard Lenten march (sublevemur).

In am reminded of the moment in the film The Passion of the Christ when Christ falls under His horrible burden of the Cross. His Mother, our Mother, recalling how once He had fallen as a child and how she had run to Him to console Him in His unexpected pain, runs to Him to give Him what support she might in His entirely expected suffering.

She ran to Him and then stood with Him.

Mary hurries also to each of us and stays by our side.

We are not in our Lenten discipline alone. When we are flagging in our efforts, when we are humbled in our failures, our Blessed Mother is our help, together with all the saints and angels of whom she is the glorious Queen.

We too can be help to others, particularly by not causing for them an occasion of temptation to break their resolve.

WARNING: I seem not to be able to watch this without choking up. I’ll bet you will too. If you are a “tough guy”, I’d shut the door.

Father, you started my day with tears! Ditto for me on that movie scene. Since I saw the movie years ago, that particular station of the cross, Jesus meets His mother, has had a special meaning for me. Because I love Mama Mary so much, I know it is painful for both of them to meet that way. If only the whole world understood it all.

”See, Mother. I make all things new”. That always brings tears.

I began tearing up just seeing the title of the clip…